By James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP Board Emeritus™, AWMA®

People often ask me what is the most common mistake that plan sponsors make, The answer is simple-assuming unnecessary fiduciary liability exposure by focusing on product rather than process. Actually, that answer applies to investment fiduciaries in general.

The courts have recognized that ERISA is essentially the codification of the common law of trusts, which in turn sets out various standards of conduct for fiduciaries. Part of the problem is that few plan sponsors have ever read or talked with an ERISA attorney about ERISA or the applicable standards. Too many plan sponsors have simply chosen to blindly follow the advice of conflicted third parties, such as mutual funds and insurance/annuity salesmen.

The courts have warned plan sponsors that reliance on third parties must be both reasonable and justified. As the court shave warned plan sponsors, reliance on commissioned sales people is rarely reasonable or justified due to the inherent conflict of interests that exists with such advisers.

We have explained that the fiduciary duties enumerated in § 404(a)(1) have three components. The first element is a “duty of loyalty” pursuant to which “all decisions regarding an ERISA plan `must be made with an eye single to the interests of the participants and beneficiaries.'” Second, ERISA imposes a “prudent man” obligation, which is “an unwavering duty” to act both “as a prudent person would act in a similar situation” and “with single-minded devotion” to those same plan participants and beneficiaries.1

Finally, an ERISA fiduciary must “`act for the exclusive purpose'” of providing benefits to plan beneficiaries.2

“[T]he duties charged to an ERISA fiduciary are `the highest known to the law.'” When enforcing these important responsibilities, we “focus[] not only on the merits of the transaction, but also on the thoroughness of the investigation into the merits of the transaction.”’3

One extremely important factor is whether the expert advisor truly offers independent and impartial advice.4

FPA and Pescitelli, therefore, are not independent analysts. FPA does not work for TWU; rather, insurance companies like Transamerica pay Pescitelli’s salary. As a broker, FPA and its employees have an incentive to close deals, not to investigate which of several policies might serve the union best. A business in FPA’s position must consider both what plan it can convince the union to accept and the size of the potential commission associated with each alternative. FPA is not an objective analyst any more than the same real estate broker can simultaneously protect the interests of both buyer and seller or the same attorney can represent both husband and wife in a divorce. 841-842 5

So, what does ERISA actually say with regard to the fiduciary duties of a plan sponsor? Section 404(a) of ERISA provides that

(a) a fiduciary shall discharge that person’s duties with respect to the plan solely in the interests of the participants and beneficiaries; for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to participants and their beneficiaries and defraying reasonable expenses of administering the plan; and with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.

(b) Investment prudence duties.

(1) With regard to the consideration of an investment or investment course of action taken by a fiduciary of an employee benefit plan pursuant to the fiduciary’s investment duties, the requirements of section 404(a)(1)(B) of the Act set forth in paragraph (a) of this section are satisfied if the fiduciary:

(i) Has given appropriate consideration to those facts and circumstances that, given the scope of such fiduciary’s investment duties, the fiduciary knows or should know are relevant to the particular investment or investment course of action involved, including the role the investment or investment course of action plays in that portion of the plan’s investment portfolio or menu with respect to which the fiduciary has investment duties; and

(ii) Has acted accordingly.

(2) For purposes of paragraph (b)(1) of this section, “appropriate consideration” shall include, but is not necessarily limited to:

(i) A determination by the fiduciary that the particular investment or investment course of action is reasonably designed, as part of the portfolio (or, where applicable, that portion of the plan portfolio with respect to which the fiduciary has investment duties) or menu, to further the purposes of the plan, taking into consideration the risk of loss and the opportunity for gain (or other return) associated with the investment or investment course of action compared to the opportunity for gain (or other return) associated with reasonably available alternatives with similar risks;

(c) Investment loyalty duties.

(1) A fiduciary may not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income or financial benefits under the plan to other objectives, and may not sacrifice investment return or take on additional investment risk to promote benefits or goals unrelated to interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income or financial benefits under the plan.

(2) If a fiduciary prudently concludes that competing investments, or competing investment courses of action, equally serve the financial interests of the plan over the appropriate time horizon, the fiduciary is not prohibited from selecting the investment, or investment course of action, based on collateral benefits other than investment returns. A fiduciary may not, however, accept expected reduced returns or greater risks to secure such additional benefits. 6

So, where do plan sponsors usually get in trouble with regard to such legal obligations?

“[W]ith the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.”

First, notice that Section 404(a)does not expressly require that a plan offer any specific investment within a plan. As is the case with most laws and regulations, ERISA is written in broad general terms in order to provide regulators with maximum flexibility to address violations on an “as needed” basis.

With the passage of SECURE and SECURE 2.0, I have been receiving calls and emails from both InvestSense clients and non-clients saying that annuity representatives have been falsely telling them that both SECURE acts require plans to offer annuities within their 401(k) plans. Simply not true. Same goes for crypto.

I have even had annuity and crypto advocates tell me that is morally wrong not to offer such investments in a plan if the plan participants wish to invest in such investments. Morally wrong…seriously?

I have been involved in fiduciary law in one way or the other since 1996. I have advised fiduciaries to use the same two question fiduciary risk management technique that I use in performing forensic analyses of actively managed funds.

1. Does ERISA expressly require that the specific investment be offered within a 401(k) or 403(b) plan? From the previous discussion, we know the answer to that question will always be “no.”

2. Would/Could inclusion of the specific investment in the plan potentially result in unnecessary fiduciary liability exposure for the plan sponsor?

The second question requires an analysis of an investment pursuant to ERISA’s prudent person standard. I am often asked to provide expert analyses with regard to actively managed mutual funds and, recently, annuities. The proper question is whether a plan sponsor’s investment selections measure up under ERISA’s prudent person standard, from a process versus product viewpoint.

Actively Managed Mutual Funds

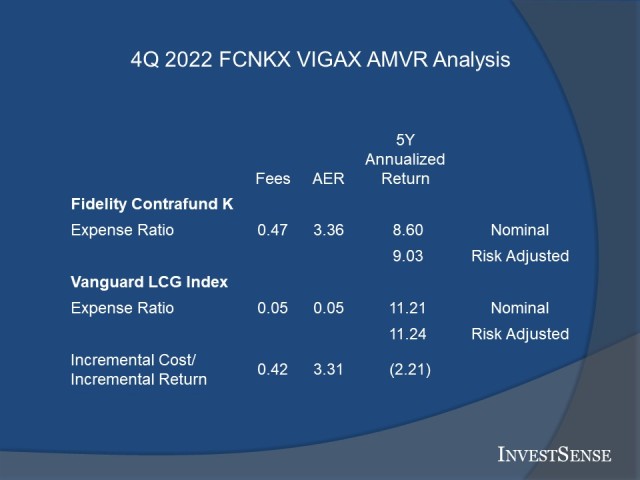

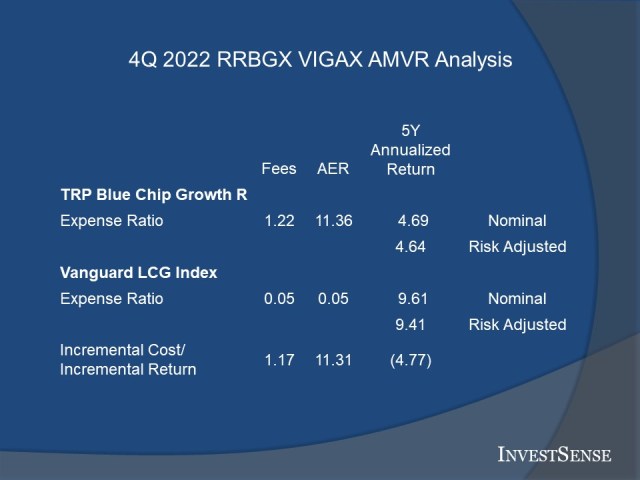

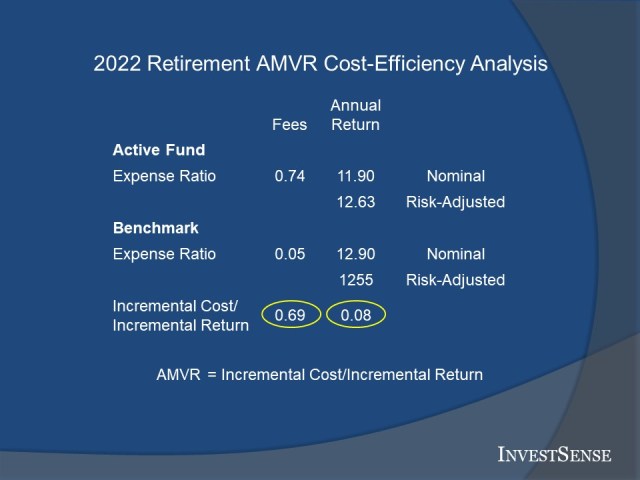

The cornerstone of my analysis of actively managed mutual funds is based on my metric, the Active Management Value Ratio (AMVR). The AMVR is simply a modified version of the well-known cost/benefit metric commonly used in numerous businesses and professions.

In this case, the AMVR is simply a visual presentation of the research of investment experts such as Nobel Laureate Dr. William F. Sharpe, Charles D. Ellis, and Burton G. Malkiel.

[T]he best way to measure a manager’s performance is to compare his or her return with that of a comparable passive alternative.7

So, the incremental fees for an actively managed mutual fund relative to its incremental returns should always be compared to the fees for a comparable index fund relative to its returns.

When you do this, you’ll quickly see that that the incremental fees for active management are really, really high—on average, over 100% of incremental returns! 8

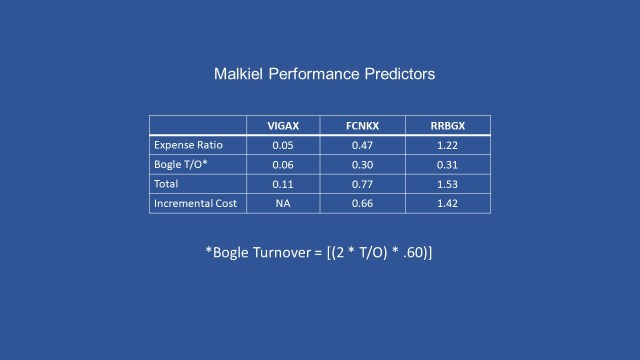

Past performance is not helpful in predicting future returns. The two variables that do the best job in predicting future performance [of mutual funds] are expense ratios and turnover. 9

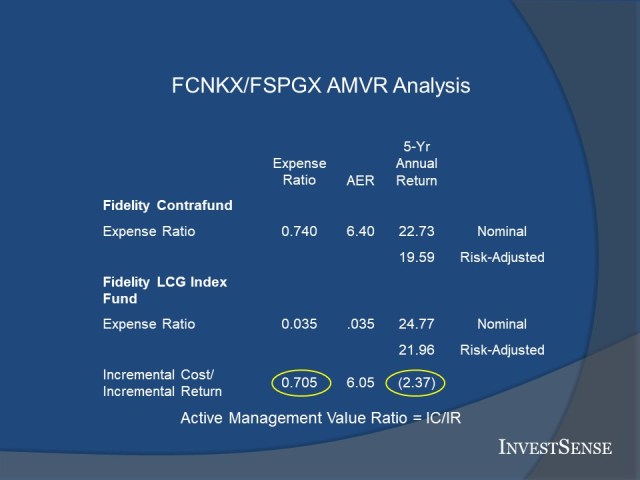

These three opinions formed the basis for the initial iteration of the AMVR. Further research led to the current version of the AMVR – AMVR 3.0 – which incorporates the research of Ross Miller and his Active Expense Ratio (AER) metric. Miller explains the importance of the AER as follows:

Mutual funds appear to provide investment services for relatively low fees because they bundle passive and active funds management together in a way that understates the true cost of active management. In particular, funds engaging in ‘closet’ or ‘shadow’ indexing charge their investors for active management while providing them with little more than an indexed investment. Even the average mutual fund, which ostensibly provides only active management, will have over 90% of the variance in its returns explained by its benchmark index.10

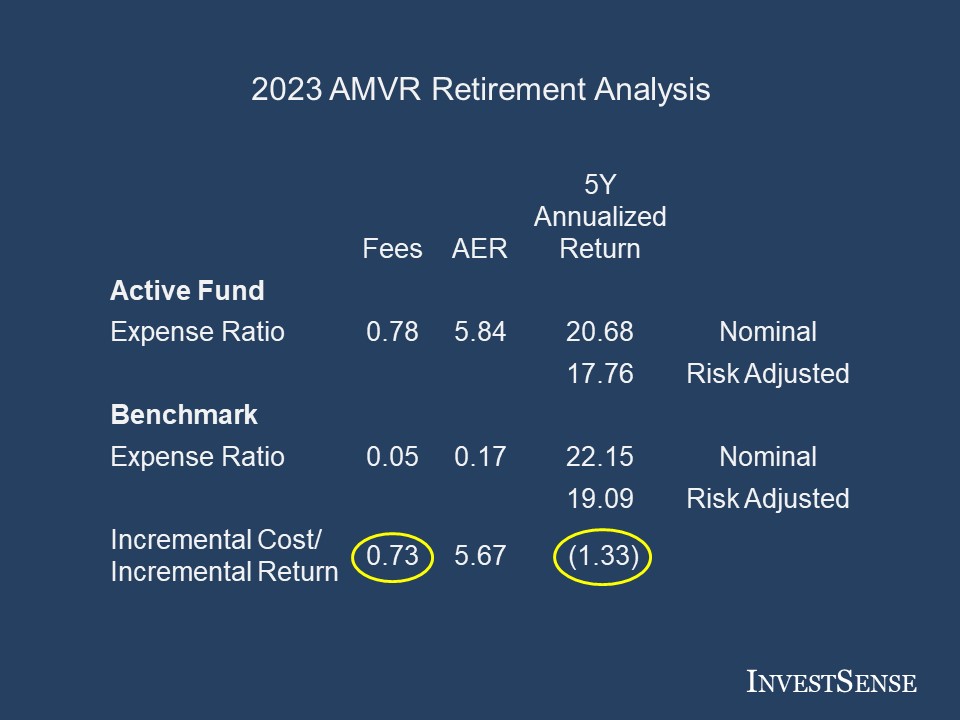

An example of the end result – AMVR 3.0 – is shown below.

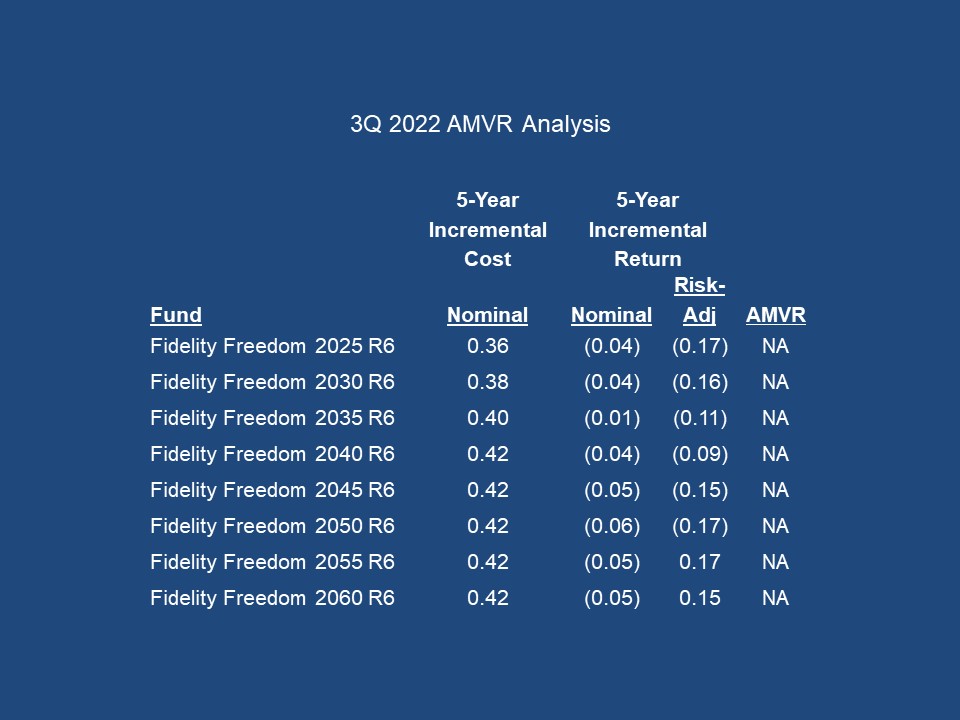

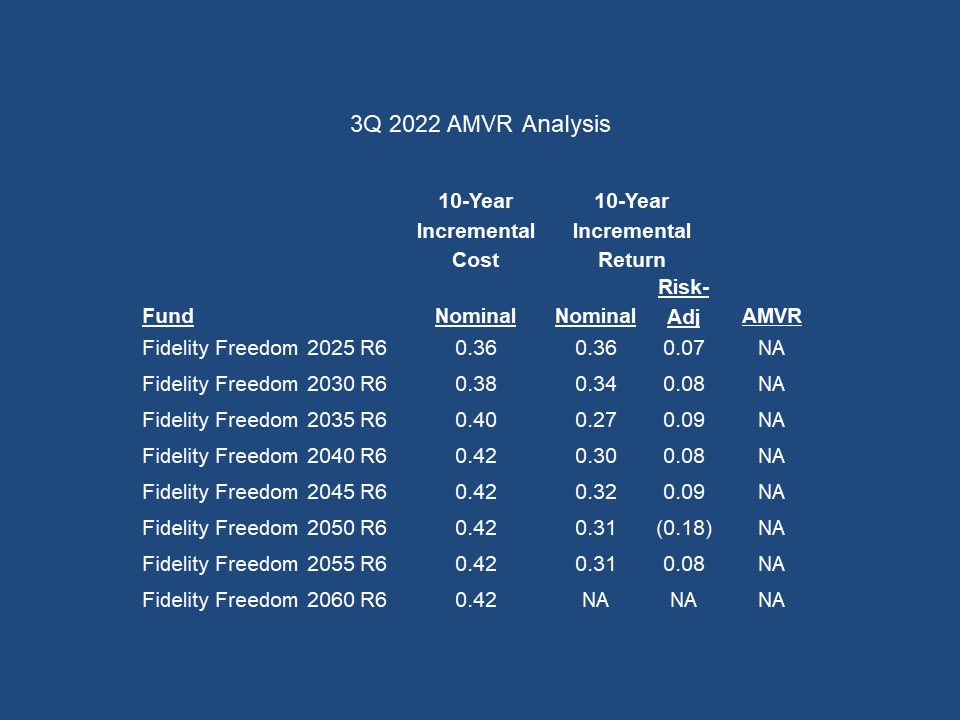

An AMVR analysis can be calculated for any time period. In this case, a five-year analysis comparing an actively managed fund and a comparable index fund shows that the actively managed fund is cost-inefficient, as it fails to provide a positive incremental return (1.33), so naturally the incremental costs exceed the incremental returns. A cost-inefficient fund is an imprudent investment under the Restatement (Third) of Trusts.

The cost-inefficiency in the example is even more serious if measured using the AER, In this case, the high incremental costs of the funds combined with the fund’s high correlation of return to the benchmark (98) results in an AER of 5.67.

The example show above is far from an anomaly. Research has consistently shown that the overwhelming majority of actively managed funds are cost-inefficient.

99% of actively managed funds do not beat their index fund alternatives over the long term net of fees.11

Increasing numbers of clients will realize that in toe-to-toe competition versus near–equal competitors, most active managers will not and cannot recover the costs and fees they charge.12

[T]here is strong evidence that the vast majority of active managers are unable to produce excess returns that cover their costs.13

[T]he investment costs of expense ratios, transaction costs and load fees all have a direct, negative impact on performance….[The study’s findings] suggest that mutual funds, on average, do not recoup their investment costs through higher returns.14

Perhaps the best advice on selection of mutual funds was offered by John Langbein, who served as the Reporter on the committee that wrote the Restatement (Second) of Trusts over fifty years ago. Shortly after the release of the revised Restatement, Langbein wrote a law review article on the new Restatement. At the end of the article, he made a bold prediction:

When market index funds have become available in sufficient variety and their experience bears out their prospects, courts may one day conclude that it is imprudent for trustees to fail to use such accounts. Their advantages seem decisive: at any given risk/return level, diversification is maximized and investment costs minimized. A trustee who declines to procure such advantage for the beneficiaries of his trust may in the future find his conduct difficult to justify.15

The AMVR provides a quick and simple process that plan sponsors can uses to reduce their risk of unnecessary and unwanted fiduciary liability exposure by ensuring the prudence of their investment choices of their plan.

Annuities

The current attempt to convince plan sponsors to include annuities inn their plans is a perfect example of the psychological tactic known as “framing.” Framing refers to how an idea is presented in order to convince someone to agree with idea.

In the case of annuities, the pitch is “guaranteed income.” However, that hardly presents all of the variables that a plan sponsor needs to consider before deciding to include annuities in their 401(k) or 403(b) plan. As usual, the devil is in the details. As the late insurance advisor Peter Katt used to warn, “at what cost?”

Key risks with annuities include excessive fees, purchasing power risk, the risk that inflation will reduce the value of annuity payments, and single equity credit risk, the risk that the annuity issuer will not be able to make the payments called for by the annuity contract. Chris Tobe, one of the co-founders of otherthis blog’s sister site, the CommonSense 401(k) Project has written some excellent posts explaining some of the risks inherent in annuities. I highly recommend that you review his posts.

And with annuities, there are other serious costs that fiduciaries have to consider, most notably the commensurate return/windfall issue If the annuity requires that the annuity owner “annuitize” the annuity contract in order to receive the promised benefit of “guaranteed income,” the annuity owner has to surrender control of both the annuity and its accumulated value, with no guarantee of a commensurate return for the surrendered value, creating the potential windfall for the annuity issuer at the expense of the annuity owner and their heirs.

Plan sponsors often overlook the potential fiduciary liability issues created by the commensurate return/windfall issue. Fiduciary law is a combination of trust law, agency law and the law of equity. A basic tenet of equity law is that “equity abhors a windfall

Annuity advocates usually respond to the commensurate return issue by pointing out that some annuities address such shortcomings by offering the annuity owner a rider that guarantees the return of the premiums they paid…for yet another fee. Studies by both the Department of Labor and the General Accountability Office have stated that each additional 1 percent in fees/costs reduced an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent over a period of twenty years.16 So, the recommendation to “just add a rider” is not a simple solution to the commensurate return issue.

While these issues present obvious potential fiduciary liability concerns for plan sponsors, there is a simple way to avoid them altogether. Remember, ERISA does not require that a plan offer any specific investment within a plan. Given the potential fiduciary liability issues discussed herein, we advise our clients not to offer annuities within their plan.

ERISA does not require plan participants to assume unnecessary fiduciary liability risk. Annuities are often complex and confusing. For example, “indexed” annuities deliberately mislead investors into believing that they may achieve the returns of a market index. However, they quickly learn that the annuity issuer will significantly reduce their actual realized return by imposing restrictions such as caps on return and “participation rates.” Artificial and arbitrary restrictions and the various methods of computing and crediting returns simply increase the potential for fiduciary mistakes/misunderstandings and, thus, the potential for increased fiduciary liability exposure. Plan participants that wish to invest in annuities would still be free to do so outside the plan.

Going Forward

Far too often, plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries unknowingly assume unnecessary and unwanted fiduciary liability exposure. This mistake is often due to a lack of knowledge and understanding as to what ERISA or trust law requires of them.

Hopefully, this post has helped plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries realize how simple ERISA and fiduciary compliance can be by focusing on fiduciary process rather than investment products. An ERISA compliant fiduciary process will both simplify the selection of investment options and help reduce fiduciary liability exposure by ensuring the selection of prudent investment products.

Hopefully, this post has also convinced the reader to further explore the AMVR metric and learn how simple it is to use the AMVR to

> reduce potential fiduciary liability exposure,

> improve the quality of plan investment options.

> potentially simplify their plan in order to reduce administrative costs and increase employee > participation in the plan.

Bottom line-A proper fiduciary process will help ensure the prudence of the plan’s investment options.

.Notes

1. Gregg v. Transportation Workers of Am. Intern, 343 F.3d 833, 841-842 (6th Cir. 2003).

2. Gregg, Ibid.

3. Gregg, Ibid.

4. Gregg, Ibid.

5. Gregg, Ibid.

6. 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404-1; 29 U.S.C. § 1104(a) ![]()

7. William F. Sharpe, “The Arithmetic of Active Investing,” available online at https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/active/active.htm

8. Charles D. Ellis, “Letter to the Grandkids: 12 Essential Investing Guidelines,” available online at https://www.forbes.com/sites/investor/2014/03/13/letter-to-the-grandkids-12-essential-investing-guidelines/#cd420613736c

9. Burton G. Malkiel, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” 11th Ed., (W.W. Norton & Co., 2016), 460.

10. Ross Miller, “Evaluating the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds,” Journal of Investment Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, 29-49 (2007) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=746926

11. Laurent Barras, Oliver Scaillet, and Russ Wermers, False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas, 65 J. FINANE 179, 181 (2010)

12. Charles D. Ellis, The Death of Active Investing, Financial Times, January 20, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/6b2d5490-d9bb-eb37a6aa8e

13. Mark Carhart, On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance, 52 J. FINANCE 57-58 (1997)

14. Philip Meyer-Braun, Mutual Fund Performance Through a Five-Factor Lens, Dimensional Funds Advisors, L.P., August 2016

15. John H. Langbein and Richard A. Posner, Measuring the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds, Journal of Investment Management, Vol 5, No. 1, First Quarter 2007 http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/498

16. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Feess abd Expenses,” (“DOL Study”). http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study”),

Copyright InvestSense, LLC 2023. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.