The six funds shown are six of the leading non-index funds that are consistently offered in U.S. domestic defined contribution plans. My development of the Active Management Value Ratio (AMVR) metric was originally based on the work of Nobel laureate Dr. William F. Sharpe and investment expert Charles D. Ellis.

Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs…. The best way to measure a manager’s performance is to compare his or her return with that of a comparable passive alternative.1

So, the incremental fees for an actively managed mutual fund relative to its incremental returns should always be compared to the fees for a comparable index fund relative to its returns. When you do this, you’ll quickly see that that the incremental fees for active management are really, really high—on average, over 100% of incremental returns.2

The current version of the AMVR, AMVR 3.0, was modified to incorporate the work of Professor Ross Miller. Miller’s Active Expense Ratio (AER) factors in the high correlation of returns often found between actively managed funds and comparable passively managed/index funds. The AER provides investors with the implicit expense ratio they are paying for an actively managed fund. The AER also helps expose actively managed funds that are arguably “closet index” funds. As Miller explained,

Mutual funds appear to provide investment services for relatively low fees because they bundle passive and active funds management together in a way that understates the true cost of active management. In particular, funds engaging in ‘closet’ or ‘shadow’ indexing charge their investors for active management while providing them with little more than an indexed investment. Even the average mutual fund, which ostensibly provides only active management, will have over 90% of the variance in its returns explained by its benchmark index.3

The 3Q 2023 5 and 10-year AMVR “cheat sheet” numbers provide an opportunity to discuss pending 401(k) litigation that may significantly impact the 401(k) management and fiduciary liability in general. The 5-year “cheat sheet” shows that two funds qualified for an AMVR score.

In order for an actively managed to be eligible for an AMVR score, it must first produce a positive incremental return relative to the passively managed benchmark. American Fund’s Washington Mutual Fund received a 5-year AMVR score of 2.94, while Vanguard’s PRIMECAP fund received a 5-year AMVR score of 2.88.

However, neither fund would qualify as being prudent under the Restatement (Third) of Trusts’ fiduciary prudence standards since their AMVR score is greater than 1.00. An AMVR greater than 1.0 indicates that the fund’s incremental costs exceed the fund’s incremental returns. InvestSense uses correlation-adjusted costs and risk-adjusted returns in calculating a fund’s AMVR score, as they provide a more accurate representation of a fund’s cost/benefit to an investor.

The 10-year “cheat sheet” shows that three funds qualified for an AMVR score. American Fund’s Washington Mutual Fund received an AMVR score of 10.36, Vanguard’s PRIMECAP fund received an AMVR score of 1.01, and Fidelity Contrafund K shares received an AMVR score of 1.78.

However, none of the funds would qualify as being prudent under the Restatement (Third) of Trusts’ fiduciary prudence standards since their AMVR score is greater than 1.00, although a strong argument can be made for Vanguard PRIMECAP.

One often overlooked benefit of a fund’s AMVR score is that it provides an easy way to determine a fund’s cost premium. In the case of the 10-year Contrafund K shares analysis, the active fund’s incremental cost was 280 basis points (2.80), while the fund’s incremental return was 157 basis points (1.57).

The financial services typically uses basis points in making comparisons. A basis point is equal to 1/100th of one percent. Contrafund’s AMVR indicates that the fund’s cost premium of 123 basis points was equal to 78 percent cost premium (AMVR of 1.78 minus 1.00, multiplied by 100).

So how does this all tie into the pending 401(k) litigation cases? The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals recently issued its much anticipated decision in Matney v. Briggs Gold of North America4. As I summarized in my earlier post, the Tenth Circuit upheld the district court’s dismissal of the plan participants’ 401(k) action claiming that the plan sponsor breached its fiduciary duties by (1) including imprudent investment options within the plan, and (2) imposing unnecessarily high fees on the participants. The Tenth Circuit basically relied on the usual “lack of meaningful benchmarks” and an interpretation of revenue sharing that had previously been rejected by other federal circuit courts of appeal.

The good news is that now the plan participants will, hopefully, apply to SCOTUS for certiorari so that the Court can establish uniform rules on both (1) the propriety of index funds as comparators in 401(k) and 403(b) litigation, and (2) the party who has the burden of proof on the causation of loss issue in such litigation. The Solicitor General submitted an amicus brief in the Brotherston case citing the common law as placing such burden of proof on a plan sponsor once the plan participants established a fiduciary breach and a resulting loss. The Department of Labor (DOL) recently submitted an amicus brief in the current Home Depot5 401(k) litigation, essentially adopting the Solicitor General’s position.

Various courts have relied on the “lack of meaningful benchmarks” theory in dismissing 401(k) litigation cases. The Tenth Circuit discussed several theories of determining whether a proposed benchmark was actually comparable to the investment option chosen by a plan, including the familiar active/passive argument. The Court also discussed the comparison of expense ratios method, including an interesting argument based on the idea that any revenue sharing generated by funds in a plan must be applied on a 1:1 basis to reduce those funds’ expense ratio on a 1:1 basis. I addressed these issues in my last post.

What I want to discuss in this post is the concept of “meaningful benchmarks” aka comparators in connection with the AMVR. The Tenth Circuit suggested that to be a meaningful comparator, plan participants must go beyond performance and factor in questionable collateral issues such as a fund’s management strategies and goals. My position is, and always will be, that such collateral issues are meaningless to plan participants and in 401(k) and 403(b) litigation. A slide I often use in my classes expresses both my position and what investors consistently tell me.

The investment industry has always argued against using risk-adjusted returns in comparing investment options, stating that you “cannot eat risk-adjusted returns.” The same argument can be made against any requirement that a fund’s strategies and goals must be factored into any fiduciary prudence assessment in connection with ERISA-related litigation. If we recognize the stated purpose of ERISA is to protect employees, then attention in any 401(k) or 403(b) litigation should be solely on a fund’s cost-efficiency, more specifically the benefit that a fund provides to a plan participant relative to the costs/fees incurred.

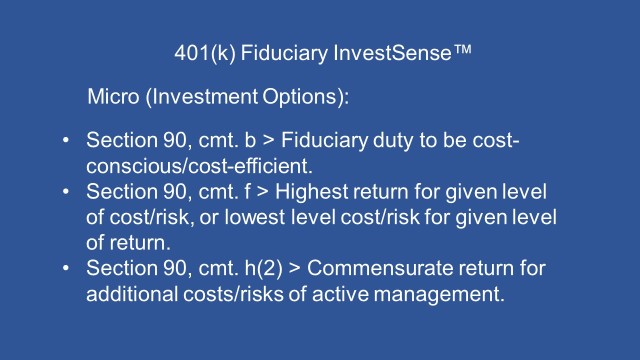

In the Tibble decision6, SCOTUS recognized the value of the Restatement of Trusts (Restatement) in resolving fiduciary questions. SCOTUS recognized that the Restatement essentially restates the common law of trusts, a standard often used by the courts. The two dominant themes running throughout the Restatement are the dual fiduciary duties of cost-consciousness and diversification within investment portfolios to reduce investment risk.

In my fiduciary risk management consulting practice, I rely heavily on five core principles from the Restatement to reduce fiduciary risk. Three of the five principles are cost-consciousness/cost-efficiency principles:

Comment h(2)’s commensurate standard is a principle that I feel very few fiduciaries do, or can, meet if they include actively managed mutual funds in their plan. Actively managed funds start from behind in comparison to comparable passive/index funds due to the extra and higher expenses they incur from management fees and trading fees. As a result, a case can be made that ERISA plaintiff attorneys could effectively use the Restatement’s commensurate return and SCOTUS’ approval of the Restatement effectively in 401(k) litigation

Advocates of active management often claim that active management provides an opportunity to overcome such cost issues. However, the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that very few do so, with most actively managed funds being able to even cover their extra costs.

99% of actively managed funds do not beat their index fund alternatives over the long term net of fees.7

Increasing numbers of clients will realize that in toe-to-toe competition versus near–equal competitors, most active managers will not and cannot recover the costs and fees they charge.8

[T]here is strong evidence that the vast majority of active managers are unable to produce excess returns that cover their costs.9

Another factor to consider in such poor performance numbers has to do with the fact that actively managed funds typically show a high correlation of returns to comaparable index funds, with many showing a r-squared number of 90 and above. Such a high correlation of returns could suggest that the active fund involved is actually a “closet index” fund, misleading investors by charging a significantly higher fee than a comparable index fund based on the alleged benefits of the fund’s active management, while actually deliberately tracking, or mirroring, a comparable market index or index fund. Such misrepresentations are arguably fraud and violations of various federal securities laws.

The Restatement and the common law of trusts seemingly resolve both the issues involved in the Matney cases in favor of beneficiaries such as the plan participants. While we wait to see if the plan participants file to seek certiorari from SCOTUS, I have previously suggested that both plan sponsors and ERISA plaintiff attorneys need to act proactively and change the paradigm to use the Active Management Value Ratio metric to analyze the fiduciary prudence of a plan’s investment options.

The AMVR “cheat sheets” consistently document the potential liability issues that plan sponsors have created fo themselves. While many plan sponsors have indicated to me that they prefer to just ignore the situation and deal with it if and when a legal action is filed, I try to explain to them that the law does not recognize “willful ignorance” as a defense.

Businesses around the world utilize cost/benefit analysis into their decision making process. I believe that plan sponsors should as well. The familiar adage that a picture is worth a thousand words should hold true in 401(k) litigation, as it is hard to believe that any court would not understand that nay investment whose incremental costs exceed its incremental benefits is not, and never will be prudent under fiduciary law, regardless of the fund’s stated strategies and goals.

When I meet a prospective client, I always show them three AMVR slides representing actual investments in their plans. In most cases, they look at the slides and realize the liability issues they face. In the sample AMVR slide shown, the estimated damages in connection with the fund would be estimated at between $2.06 and $6.57 a share, compounded annually. Then repeat the analysis for every investment option within the plan.That explains why settlements are usually reported in terms of millions of dollars.

One of my mantras to my fiduciary clients is “commensurate returns and common sense” are a strong combination in fiduciary prudence cases. Restatement Section 90, comment h(2) discusses commensurate return in terms of the extra costs and risk plan participants be asked to incur in a plan’s investment options. That explains why InvestSense uses risk-adjusted returns and correlation-adjusted costs in calculating AMVR scores and fiduciary prudence. Common sense should indicate that cost-inefficient investments are never prudent.

If SCOTUS does hear the Matney case and rule that plan sponsors bear the burden of proving that they did not cause any losses suffered by plan participants, this might well be the type of evidence that plan sponsors will have to counter in order to win the case. In most cases, I do not believe that plan sponsors will be able to overcome the power of “humble arithmetic” and the simplicity, yet persuasiveness, of the AMVR evidence.

Going Forward

I believe that SCOTUS will use either the Matney case or the Home Depot case to resolve the inequitable division of the federal courts on the issue of which party in 401(k) litigation has the burden of proof on the issue of causation of loss. I also believe the Court will cite the Restatement to establish that mutual funds cannot be summarily be rejected as legally viable comparators in ERISA litigation, at least for the purposes of prematurely dismissing meritorious cases.

Citing the Sacerdote10 decision, the DOL made an interesting comment in its recent amicus brief in the Home Depot 401(k) action:

If a plaintiff succeeds in showing that “no prudent fiduciary” would have taken the challenged action, they have conclusively established loss causation, and there is no burden left to “shift” to the fiduciary defendant.11

I believe that once SCOTUS rules in the Matney and/or Home Depot cases, courts, attorneys, and plan sponsors will soon recognize the AMVR as a valuable fiduciary risk management analytical tool towards that can establish both the requisite fiduciary breach and resulting loss, effectively establishing that “no prudent fiduciary” would have chosen a cost-inefficient actively managed mutual fund.

Notes

1. William F. Sharpe, “The Arithmetic of Active Investing,” available online at https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/active/active.htm.

2. Charles D. Ellis, “Letter to the Grandkids: 12 Essential Investing Guidelines,” available online at https://www.forbes.com/sites/investor/2014/03/13/letter-to-the-grandkids-12-essential-investing-guidelines/#cd420613736c.

3. Ross Miller, “Evaluating the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds,” Journal of Investment Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, 29-49.

4. Matney v, Barrick Gold of North America, No. 22-4045, September 6, 2023 (10th Circuit Court of Appeals (Matney 10th Circuit).

5. Pizarro v. Home Depot, Inc., No. 22-13643 (11th Cir. 2022)

6. Tibble v. Edison International, 135 S. Ct. 1823 (2015).

7. Laurent Barras, Olivier Scaillet and Russ Wermers, False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas, 65 J. FINANCE 179, 181 (2010).

8. Charles D. Ellis, The Death of Active Investing, Financial Times, January 20, 2017.

9. Philip Meyer-Braun, Mutual Fund Performance Through a Five-Factor Lens, Dimensional Fund Advisors, L.P., August 2016.

10. Sacerdote v. New York University, 9 F.4th 95 (2d Cir. 2021).

11. Department of Labor amicus brief in Pizarro v. Home Depot, Inc., No. 22-13643 (11th Cir. 2022) (Amicus Brief), 26. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/SOL/briefs/2023/HomeDepot_2023-02-10.pdf

Copyright InvestSense, LLC 2023. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.