The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals finally issued its much-anticipated decision in Matney v. Briggs Gold of North America1 (Matney). As expected, the Court upheld the district court’s dismissal of the case. The good news is that the Tenth Circuit’s publication of the decision allows the plan participants to apply for certiorari so that SCOTUS can hear an appeal of the Tenth Circuit’s decision

I believe that SCOTUS will grant certiorari and hear the casel if the participants apply for cert given the importance of ERISA in people’s lives and the fact that a split currently exists within the federal court on several critical aspects of ERISA. I also believe that the Court will grant cert in Matney in order to resolve two important questions that were first presented to the Court in the Brotherston case.2

The Court denied certiorari in Brotherston based upon the advice of the Solicitor General of the United States due the fact that the case was still ongoing at that time. While the Solicitor General recommended that SCOTUS not grant certiorari, the Solicitor General stated that the First Circuit Court of Appeals had correctly decided both questions involved and then took the time to provide an excellent analysis of the issues.3

I maintain that Matney is essentially a revisiting of the Brotherston case, as the two key issues in Matney and Brotherston are identical. For that reason, I am going to address the Tenth Circuit’s decision more in terms of the Solicitor General’s excellent amicus brief in Brotherston rather than the Tenth’ Circuit’s opinion, as I believe it will provide a better perspective on SCOTUS’ ultimate decision in the case.

SCOTUS and the Tibble decision

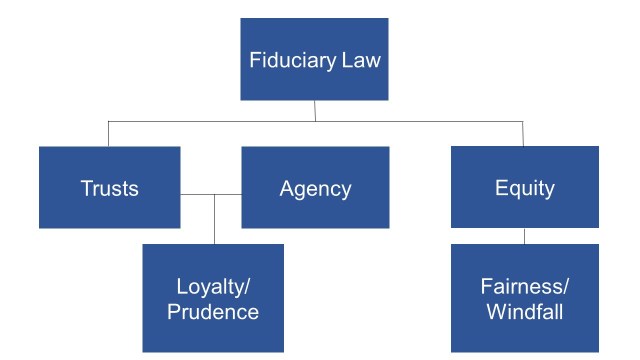

The Tibble decision4 is often cited as setting forth the framework that SCOTUS and other courts use in deciding ERISA cases.

An ERISA fiduciary must discharge his responsibility “with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence” that a prudent person “acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters” would use. We have often noted that an ERISA fiduciary’s duty is “derived from the common law of trusts.” In determining the contours of an ERISA fiduciary’s duty, courts often must look to the law of trusts. We are aware of no reason why the Ninth Circuit should not do so here.5

Substitute “Tenth Circuit” for “Ninth Circuit,” and I believe you could have the opening paragraph in a SCOTUS’ Matney decision.

As I mentioned earlier, both Matney and Brotherston involve the same two questions:

1. Are comparable market indices and index funds acceptable comparators when the prudence of actively managed mutual funds is an issue in 401(k)/403(b) litigation?

2. Which party bears the burden of proof on the issue of causation of loss in 401(k)/403(b) litigation?

Comparable Index Funds as Comparators

The Solicitor General opined that the First Circuit Court of Appeals had correctly ruled in Brotherston that index funds are not, as a matter of law, improper comparators for determining whether an ERISA fiduciary breached their fiduciary duties and calculating the resulting damages.6

The Solicitor General noted that determining losses in an ERISA action follows the same procedure as in other fiduciary breach actions, comparing ‘the actual performance of the plan investments and the performance that otherwise would have taken place.” Citing Section 100, comment b(1) of the Restatement, the Solicitor General stated that appropriate comparators may include

[R]eturn rates of one or more suitable common trust funds, or suitable index mutual funds or market indexes (with such adjustments as may be (sic) appropriate.7

The Solicitor General noted that the Brotherston court cited other legal support for the use of index funds as valid comparators in calculating losses due a fiduciary breach.

Finally, the Restatement specifically identifies as an appropriate comparator for loss calculation purposes return rates of one or more … suitable index mutual funds or market indexes (with such adjustments as may be appropriate).8

Moreover, any fiduciary of a plan such as the Plan in this case can easily insulate itself by selecting well-established, low-fee and diversified market index funds. And any fiduciary that decides it can find funds that beat the market will be immune to liability unless a district court finds it imprudent in its method of selecting such funds, and finds that a loss occurred as a result. In short, these are not matters concerning which ERISA fiduciaries need cry ‘wolf.’9

The Solicitor General noted that while the Restatement does not support the absolute rejection of comparable index funds as comparators for assessing fiduciary prudence and the establishing the requisite financial losses, the question as to the appropriateness of the funds chosen remained a question of fact for determination at trial.10

One aspect of establishing fiduciary imprudence and resulting losses in connection with actively managed mutual funds that courts and plan sponsors frequently overlook is the Restatement’s “commensurate return” position. The Restatement states that the use of actively managed funds and active management strategies is imprudent unless the fiduciary can objective predict that the investment in question can be expected to provide a commensurate return for the extra costs and risks assumed by beneficiaries/plan participants.

Studies have consistently shown that the overwhelming majority of actively managed funds fail to provide investors with a commensurate return, as most actively managed funds are cost-inefficient, failing to even cover their costs.

99% of actively managed funds do not beat their index fund alternatives over the long term net of fees.11

Increasing numbers of clients will realize that in toe-to-toe competition versus near–equal competitors, most active managers will not and cannot recover the costs and fees they charge.12

[T]here is strong evidence that the vast majority of active managers are unable to produce excess returns that cover their costs.13

[T]he investment costs of expense ratios, transaction costs and load fees all have a direct, negative impact on performance….[The study’s findings] suggest that mutual funds, on average, do not recoup their investment costs through higher returns.14

The cost-inefficiency of most actively managed funds is even more pronounced if the correlation of returns between many actively managed and comparable passively managed funds is factored in. Ross Miller created a metric, the Active Expense Ratio, which measures the impact of correlation of returns in such situations. Miller’s research determined that once correlation of returns is considered, the effective costs investors pay is often 400-500 percent higher than the active fund’s stated expense ratio.15 This would obviously make it that much more difficult for plan sponsors to satisfy the Restatement’s “commensurate return” standard.

John Langbein, the reporter for the committee that drafted the Restatement (Second) of Trusts, had warned in 1976 that

When market index funds have become available in sufficient variety and their experience bears out their prospects, courts may one day conclude that it is imprudent for trustees to fail to use such accounts. Their advantages seem decisive: at any given risk/return level, diversification is maximized and investment costs minimized. A trustee who declines to procure such advantage for the beneficiaries of his trust may in the future find his conduct difficult to justify.16

Burden of Proof as to Causation of Loss

As to the burden of proof on causation, the Solicitor General stated that

The ‘default rule’ in ordinary civil litigation when a statute is silent is that ‘plaintiffs bear the burden or persuasion regarding the essential aspects of their claims. But ‘the ordinary default rule, of course, admits of exceptions’17

The Solicitor General noted that one such exception applies under the law of trusts due to the high standards of conduct required of fiduciaries under the law. Citing both the Restatement and a highly respected treatise on trust law, the Solicitor General stated that

Under trust law, “when a beneficiary has succeeded in proving that the trustee has committed a breach of trust and that a related loss has occurred, the burden shift to the trustee to prove that the loss would have occurred in the absence of the breach.’18

In further support of its position, the Solicitor General noted that the burden shifting on the issue of causation furthers the stated purposes of ERISA.

In trust law, burden shifting rests on the view that ‘as between innocent beneficiaries and a defaulting fiduciary, the latter should bear the risk of uncertainty as to the consequences of its breach of duty. ERISA likewise seeks to ‘protect *** the interests of participants in employee benefit plans’ by imposing high standards of conduct on plan fiduciaries. Indeed, in some circumstances, ERISA reflects congressional intent to provide more protections than trust law. Applying trust law’s burden-shifting framework, which can serve to deter ERISA fiduciaries from engaging in wrongful conduct, thus advances ERISA’s protective purposes.19

The Solicitor General noted that SCOTUS has recognized that in some cases, shifting the burden on the issue of causation to plan sponsors furthers the goals and purposes of ERISA by allowing the plan sponsors to establish “facts peculiarly within the knowledge of” one party.20

More importantly, we have many decades of experience with the allocation of the burden of proof called for routinely by trust law, with no evidence of any particular difficulties, unfairness, or costs in applying that rule in the few cases in which it actually makes a difference.21

The Department of Labor’s recent amicus brief in the current Hom Depot 401(k) litigation arguably resolved the burden of proof on causation debate by citing the Sacerdote decision in suggesting that

If a plaintiff succeeds in showing that ‘no prudent fiduciary” would have taken the challenged action, they have conclusively established loss causation, abnd there is no burden left to ‘shift’ to the fiduciary defendant.22

Winds of Further Change

Assuming that Matney applies for certiorari, I believe that SCOTUS will, and should, grant certiorari. The current division within the federal courts on the two questions involved in Matney have essentially made a mockery of ERISA and the fundamental protections guaranteed by the statute. ERISA’s guarantees and protections are far too important to employees to be handled so cavalierly.

One of the primary areas of contention has to do with procedural matters, specifically the relative requirements of the parties in connection with a motion to dismiss. Defendants in civil litigation typically file motions to dismiss in order to reduce costs and avoid the transparency of discovery.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals Sacerdote v. New York University case23 involved a number of the same issues involved in Matney, including revenue sharing. The court also provided an excellent analysis of the fiduciary standard and the resulting procedural issue in 401(k) litigation in general.

[The fiduciary prudence] standard focuses on a fiduciary’s conduct in arriving at an investment decision, not on its results, and asks whether a fiduciary employed the appropriate methods to investigate and determine the merits of a particular investment.24

A claim for breach of the duty of prudence will “survive a motion to dismiss if the court, based on circumstantial factual allegations, may reasonably infer from what is alleged that the process was flawed” or “that an adequate investigation would have revealed to a reasonable fiduciary that the investment at issue was improvident.”25

Plaintiffs allege that this information was included in fund prospectuses and would have been available to inquiring fiduciaries when the fiduciaries decided to offer the funds in the Plans. In sum, plaintiffs have alleged “that a superior alternative investment was readily apparent such that an adequate investigation” —simply reviewing the prospectus of the fund under consideration—”would have uncovered that alternative.” On review of a motion to dismiss, we must draw reasonable inferences from the complaint in plaintiffs’ favor.26

While the plausibility standard requires that facts be pled “permit[ting] the court to infer more than the mere possibility of misconduct,” we do not require an ERISA plaintiff “to rule out every possible lawful explanation for the conduct he challenges.” To do so “would invert the principle that the complaint is construed most favorably to the nonmoving party” on a motion to dismiss.27

Although plaintiffs bear the burden of proving a loss, the burden under ERISA shifts to the defendants to disprove any portion of potential damages by showing that the loss was not caused by the breach of fiduciary duty. This approach is aligned with the Supreme Court’s instruction to “look to the law of trusts” for guidance in ERISA cases. Trust law acknowledges the need in certain instances to shift the burden to the trustee, who commonly possesses superior access to information.28

When I compare some of the recent dismissals of 401(k)/403(b) actions in the context of the clear standards set out in comments b(1) and f of Section 100 of the Restatement, my initial reaction is to recall Simon Sinek’s outstanding book, “Start With Why.”29

The referenced Restatement sections appear to be necessary, objective and fair. In too many cases, the rash of dismissals appear to be deliberately and unnecessarily draconian and arguably designed to deny plan participants their ERISA’s protections by preventing transparency. some courts have noticed this trend.

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals is not necessarily known as an advocate for plan participants. And yet, Chief Judge Sutton addressed the inequitability of the noticeable dismissal trend in certain federal circuits, especially those requiring plan participants to plead and prove the mental processes of plan sponsors and plan investment committees without allowing plan participants to have the discovery needed to discover what processes were used in selecting and monitoring the plan’s investment options.

In rejecting the plan’s arguments on the prudence of selecting actively managed funds for a fund based on the purported benefits of revenue sharing they provided, Judge Sutton adopted a common sense, fundamental fairness argument.

But at the pleading stage, it is too early to make these judgment calls. ‘In the absence of further development of the facts, we have no basis for crediting one set of reasonable inferences over the other. Because either assessment is plausible, the Rules of Civil Procedure entitle [the three employees] to pursue [their imprudence] claim (at least with respect to this theory) to the next stage….’30

This wait-and-see approach also makes sense given that discovery holds the promise of sharpening this process-based inquiry. Maybe TriHealth ‘investigated its alternatives and made a considered decision to offer retail shares rather than institutional shares’ because ‘the excess cost of the retail shares paid for the recordkeeping fees under [TriHealth’s] revenue-sharing model….’ Or maybe these considerations never entered the decision-making process. In the absence of discovery or some other explanation that would make an inference of imprudence implausible, we cannot dismiss the case on this ground. Nor is this an area in which the runaway costs of discovery necessarily cloud the picture. An attentive district court judge ought to be able to keep discovery within reasonable bounds given that the inquiry is narrow and ought to be readily answerable.31

Revenue Sharing

Revenue sharing is a much discussed issue in current 401(k)/403(b) litigation…and with good reason. In my opinion, Matney is a perfect example of the issues involved with revenue sharing and a perfect example of why SCOTUS needs establish a uniform standard on the issue of which party bears the burden of proof on the issue of causation.

Both the district court and the Tenth Circuit relied heavily on their accusation that the plan participants misrepresented the expenses ratios of investment options within the plan that provided revenue sharing. Both courts seemed to argue that the plan participants were obligated to reduce such funds’ expense ratios on a one-to-one basis by the stated revenue sharing amounts.

The attempt by both Matney courts to use revenue sharing to reduce a fund’s expense ratio is totally inconsistent with the Seventh Circuit’s acknowledgment that such attempts to offset expense ratios with revenue sharing payments on a one-to-one basis are improper. In another example of the “fundamental fairness” trend, the Seventh Circuit rejected the district court’s one-to-one offset argument, pointing out that

The problem is that the Form 5500 on which Albert relies does not require plans to disclose precisely where money from revenue sharing goes. Some revenue sharing proceeds go to the recordkeeper in the form of profits, and some go back to the investor, but there is not necessarily a one-to-one correlation such that revenue sharing always redounds to investors’ benefit. Albert’s ‘net investment expense to retirement plans theory’ assumes that there is such a correlation; if that assumption is wrong, then simply subtracting revenue sharing from the investment-management expense ratio does not equal the net fee that plan participants actually pay for investment management.32

I have argued that in cases where revenue sharing is distributed among various cost contributors, far too often the resulting situation is one in which the plan participants are effectively victimized twice, once in simply reducing excessive bookkeeping costs that remain so even after credited with a portion of revenue sharing, then again in leaving plan participants burdened with over-priced, consistently underperforming, i.e., cost-inefficient, actively managed mutual funds. Such a situation is the anti-thesis of fiduciary prudence and the stated purpose of ERISA.

The Second Circuit addressed the fiduciary issues involved with revenue sharing in the Sacerdote case, insight that is equally applicable to the revenue sharing issues in Matney.

The fact that one document purports to memorialize a discussion about whether or not to offer retail shares does not establish the prudence of that discussion or its results as a matter of law.33

We have no quarrel with the general concept of using retail shares to fund revenue sharing. But, there was no trial finding that the use here of all 63 retail shares to achieve that goal was not imprudent. Simply concluding that revenue sharing is appropriate does not speak to how the revenue sharing is implemented in a particular case. We do not know, for example, whether revenue sharing could prudently be achieved with fewer retail shares.34

The Tenth Circuit’s presumptions and premature decisions with regard to the case’s revenue sharing issues may ultimately prove to be the Matney decision’s fatal flaw.

Going Forward

When the Tenth Circuit’s Matney decision was first announced, I received numerous email assuming that I would be upset since, allegedly, my previous Matney-related posts had been proven wrong.

The Matney decision should not have surprised anyone familiar with the Tenth Circuit’s precedent in this area. I just wanted an actual decision so that the plaintiff could begin the certiorari process. As for being wrongI have been wrong before and probably will be again. Then again, I have not heard the fat lady sing yet. If SCOTUS holds true to Tibble and its other ERISA fiduciary prudence decisions, she may never do so.

In the original Matney decision35, the district court recognized that the selection process, not the ultimate performance of the product chosen by a plan, is the key issue in 401(k)/403(b) litigation. Two statements in the Tenth Circuit’s decision particular drew my attention:

(1) “circumstantial factual allegations ‘must give rise to a ‘reasonable inference’ that the defendant committed the alleged misconduct, thus ‘permit[ting] the court to infer more than the mere possibility of misconduct,”36 and

(2) “[t]o show that ‘a prudent fiduciary in like circumstances’ would have selected a different fund based on the cost or performance of the selected fund, a plaintiff must provide a sound basis for comparison—a meaningful benchmark.”37 (emphasis added)

Change “cost or performance” to “cost and performance” and I believe the letter and spirit of ERISA can be easily, and uniformly, accomplished. People who follow my posts are well aware of my position that the relative cost-efficiency of a fund, not its classification as active or passive, not a fund’s stated goals/strategies, should be the key factor in determining whether a plan sponsor or any other investment fiduciary has breached their fiduciary duties.

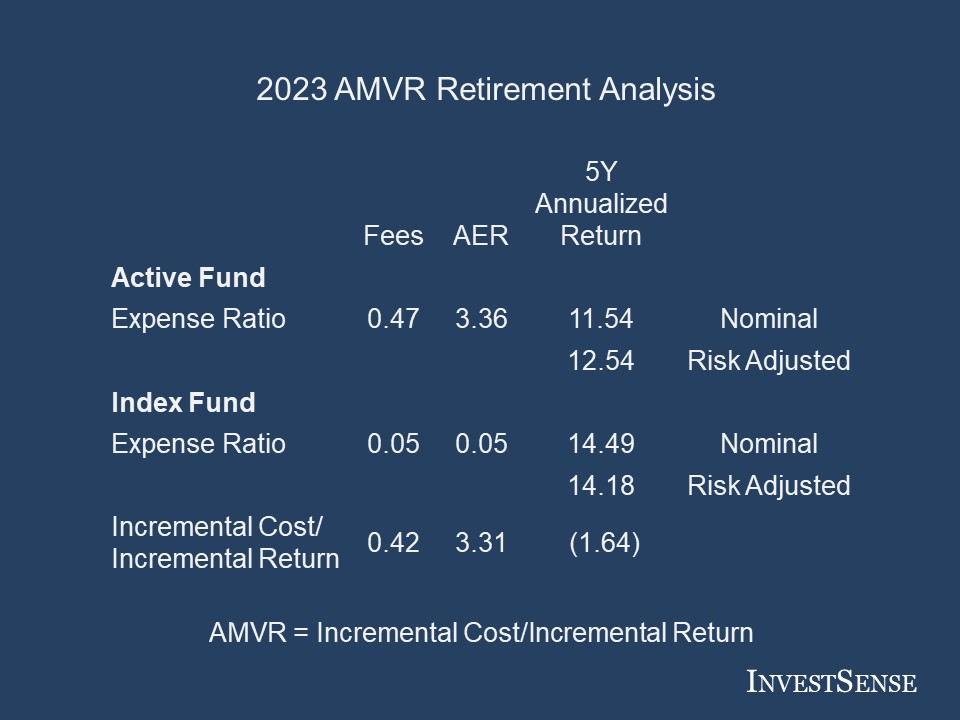

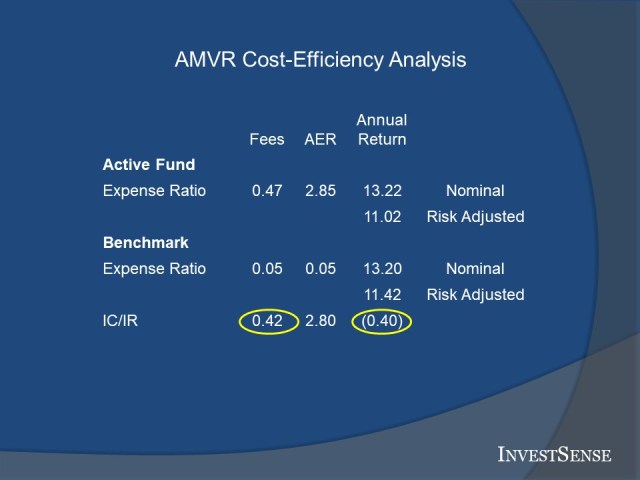

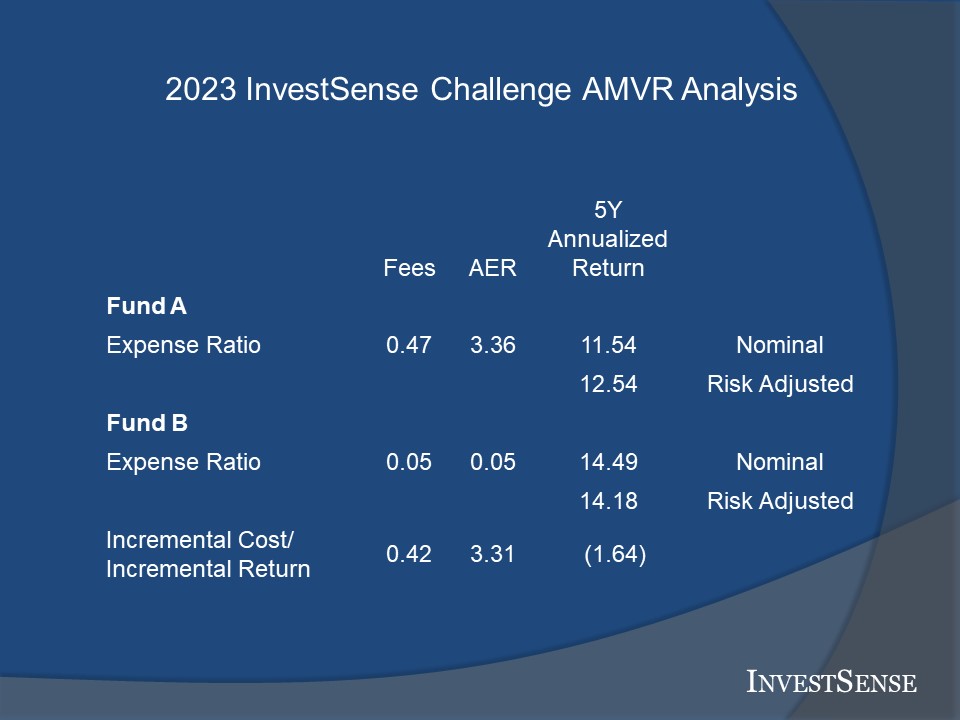

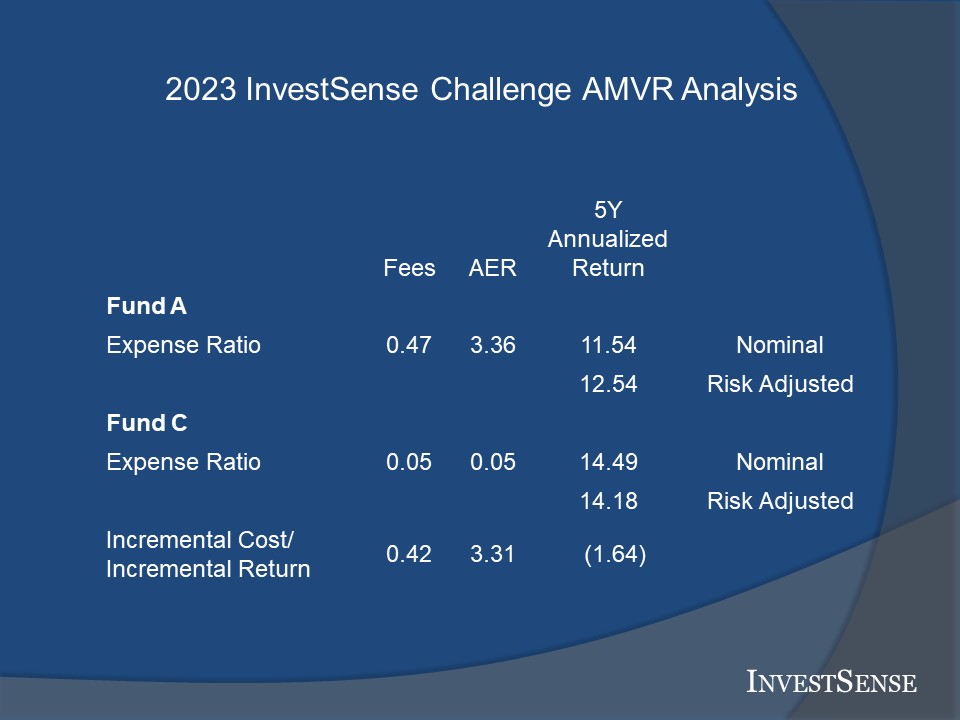

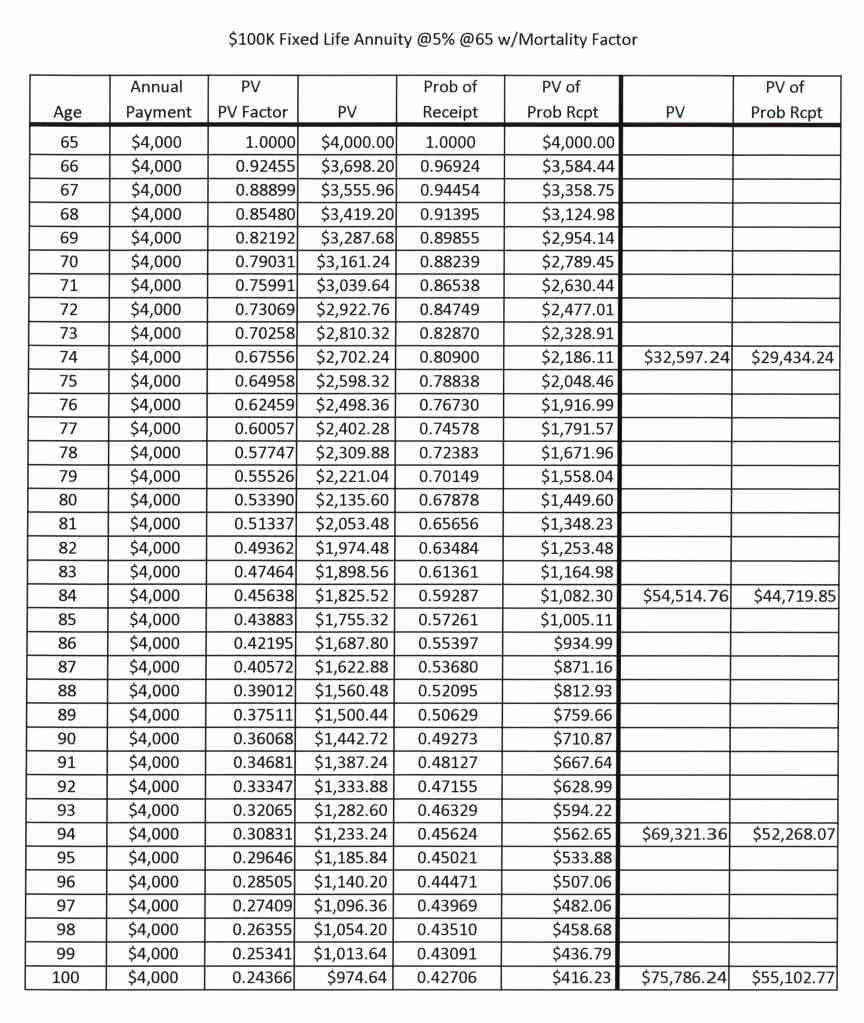

In the Hughes reconsideration decision38, the Seventh Circuit noted that “cost-consciousness management is fundamental to prudence in the investment function. My Active Management Value Ratio (AMVR) metric provides a simple method of assessing the cost-efficiency of a fiduciary’s decisions. A sample of an AMVR analysis slide is shown below.

The slide clearly establishes a “reasonable inference” of a fiduciary breach, clearly showing the cost-inefficiency of the actively managed mutual fund relative to a comparable index fund, based on the actively managed fund’s incremental cost and return. The combination of the active fund’s relative underperformance (opportunity cost) and the fund’s incremental expense ratio cost could then be used to estimate both the loss and damages caused by the plan sponsor’s fiduciary breach.

The AMVR itself is essentially the basic cost/benefit equation, using incremental cost/return as the input data. The AMVR calculation itself is obtained by dividing an active fund’s incremental cost by its incremental return. An AMVR greater than “1.0” indicates that the actively managed fund is cost-efficient.

Plan sponsors, attorneys and courts can then see the extent of the cost-inefficiency, the “imprudence premium,” being reflected in the amount by which a fund’s AMVR score exceeds “1.0,” e.g., 1.50 indicates an imprudent premium of 50 basis points/50 percent. Estimated liability exposure and/or potential legal damages can then be calculated using the DOJ’s and GAO’s findings that each additional 1 percent in costs/fees reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent over a 20-year period.39

In the example shown, the fund’s negative incremental return automatically makes the fund an imprudent choice relative to the comparable index fund. While some may want to argue differences in strategies and goals, ERISA and the AMVR ignore the meaningless collateral arguments and focus on the ultimate benefit, if any, provided to the plan participants.

The example demonstrates that whatever the active fund’s strategies and goals may have been, they ultimately proved to be imprudent relative to the performance of the comparable benchmark, failing to provide an investor with a commensurate return for the additional costs and risks. Using the slide, the combined investment costs would have resulted in a loss of between $2.06 to $7.00 per share, compounded annually. Combining the AMVR slide and the findings of the DOL and GAO also shows that an investment in the active fund would have resulted in a plan participant suffering a minimum projected 34 percent loss in end-return over a 20-period relative to the index fund option.

Final Thoughts

If SCOTUS holds true to the position it announced in Tibble, the Restatement arguably provides a simple answer to the two questions posed in the Matney case.

1. Are comparable market indices and index funds acceptable comparators when the prudence of actively managed mutual funds is an issue in 401(k)/403(b) litigation?

Answer: Section 100, cmt b(1) of the Restatement recognizes the validity of market indices and index funds as comparators in ERISA litigation. The Solicitor General and the First Circuit’s Brotherston do so as well.

2. Which party bears the burden of proof on the issue of causation of loss in 401(k)/403(b) litigation?

Answer: Section 100, comment f, of the Restatement provides as follows:

[W]hen a beneficiary has succeeded in proving that the trustee has committed a breach of duty and that a related loss has occurred, we believe that the burden of persuasion ought to shift to the trustee to prove, as a matter of defense, that he loss would have occurred in the absence of a breach.40

As the Solicitor General, the Department of Labor, and the First Circuit’s Brotherston decision have all pointed out, this position is consistent with the common law of trusts.

At first glance, this would not appear to be a difficult decision for SCOTUS if they remain consistent with their previous decision in Tibble. Since the two key questions are not directly addressed by ERISA, the court would turn to the Restatement.

As noted herein, the Restatement does clearly address and answer both questions. Furthermore, several circuits have addressed both questions and the exact scenarios involved in Matney and have provided practical, fair, and well-reasoned decisions that are consistent with both ERISA, the Restatement, and the common law of trusts.

The ongoing division within the federal courts on ERISA issues, and the unwillingness of some courts to adopt the Restatement’s clear and equitable standards, reminds me of a quote by the late General Norman Schwarzkopf that I frequently used in my closing argument to a jury

The truth of the matter is that you always know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it.

Hopefully, SCOTUS will be provided with the opportunity to do so by simply combining the Restatement with a little common sense and “humble arithmetic.”

Notes

1. Matney v, Barrick Gold of North America, No. 22-4045, September 6, 2023 (10th Circuit Court of Appeals (Matney 10th Circuit).

2. Solicitor General’s Brotherston amicus brief , 6-7. (Amicus brief)

3. Brotherston v. Putnam Investments, LLC, 907 F.3d 17 (1st Cir. 2018). (Brotherston)

4. Tibble v. Edison International, 135 S. Ct. 1823 (2015).

5. Amicus brief, 19.

6. Amicus brief, 20.

7. Amicus brief, 20.

8. Amicus brief, 20.

9. Amicus brief, 39.

10. Amicus brief, 19.

11. Laurent Barras, Olivier Scaillet and Russ Wermers, False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas, 65 J. FINANCE 179, 181 (2010).

12. Charles D. Ellis, The Death of Active Investing, Financial Times, January 20, 2017.

13. Philip Meyer-Braun, Mutual Fund Performance Through a Five-Factor Lens, Dimensional Fund Advisors, L.P., August 2016.

14.. Mark Carhart, On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance, 52 J. FINANCE, 52, 57-8 (1997).

15. Ross Miller, “Evaluating the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds,” Journal of Investment Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, 29-49.

16. John H. Langbein and Richard A. Posner, Measuring the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds, Journal of Investment Management, Vol 5, No. 1, First Quarter 2007. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/498

17. Amicus brief, 8.

18. Amicus brief, 8. (citing the Restatement (Third) of Trusts, Section 100, comment f (2012)

19. Amicus brief, 10-11.

20. Amicus brief, 11.

21. Brotherston, 39.

22. DOL’s Amicus brief in Pizarro v. Home Depot, 26.

23. Sacerdote v. New York Universit, 9 F.4th 95 (2d Cir. 2021). (Sacerdote)

24. Sacerdote, 107.

25. Sacerdote, 108.

26. Sacerdote, 108.

27. Sacerdote, 108.

28. Sacerdote, 113.

29. Simon Sinek, “Start With Why,” (Portfolio:London 2009).

30. Forman v. TriHealth, Inc., 40 F.4th 443, 450 (6th Cir. 2022). (TriHealth)

31. TriHealth, 453.

32. Albert v. Oshkosh Corp., 47 F.4th 570, 581 (7th Cir. 2022).

33. Sacerdote, 111.

34. Sacerdote, 111.

35. Matney v. Briggs Gold of North America, Case No. 2:20-cv-275-TC (C.D. Utah 2022).

36. Amicus Brief, 8.

37. Amicus brief, 21.

38. Hughes v. Northwestern University, No. 18-2569 (7th Cir. 2022), 14 (“So “cost-conscious management is fundamental to prudence in the investment function,…” (citing RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 90, cmt. B; see also id. § 88, cmt. A (“Implicit in a trustee’s fiduciary duties is a duty to be cost- No. 18-2569 15 conscious.”). “Wasting beneficiaries’ money is imprudent.” UNIF. PRUDENT INVESTOR ACT § 7, cmt. (UNIF. L. COMM’N 1995).

39. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study).

40. Restatement of the Law Third, Trusts copyright © 2007 by The American Law Institute. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.