By James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP Board Emeritus™, AWMA®

Seems that social media and trade publications are focused on the issue of “guaranteed lifetime income” options within ERISA plans, with various studies indicating that plan participants would be interested in a source of guaranteed income during retirement. That response should not come as a surprise to anyone.

Would the results be different if the question was framed differently by adding material information. Framing refers to presenting situations in such a way as to influence an individual’s response by appealing to the individual’s cognitive biases. A primary example is to present a scenario where one response will result in gain, while the other response will result in a loss.

So, presenting a poll or the results of a study which indicates that retirees would be interested in a source of guaranteed lifetime income during retirement, or at any time for that matter, is hardly earth shattering. However, what would be the likely results if we frame the same question slightly differently to disclose additional requirements and/or disadvantages, such as the following:

Would you be interested in a product that can guarantee you income for life? The only requirement would be that to receive the lifetime stream of income, you will have to surrender both control of the product and the accumulated value within the product to the company offering the product, with no guarantee of receiving a commensurate return in exchange for such concessions, as well as agreeing that the company offering the product or other third parties, not your heirs, will receive any residual value in your account when you die.

I have never had one person respond positively to my version of the “guaranteed lifetime income”/annuity sales pit.ch During my compliance days, my brokers became very familiar with my mantra – “all God’s children do not need an annuity.” A well-known saying within the annuity industry is that “annuities are sold, not bought.” Plan sponsors should remember that saying and the reasoning behind it.

Annuity advocates will often point out that annuities often offer so-called “riders” that do guarantee a return of the annuity owner’s principal to the annuity owner’s heirs…for an additional price. With annual fees within an annuity often running two percent or more, the additional fee for “riders” serves to further reduce an annuity owner’s end-return.

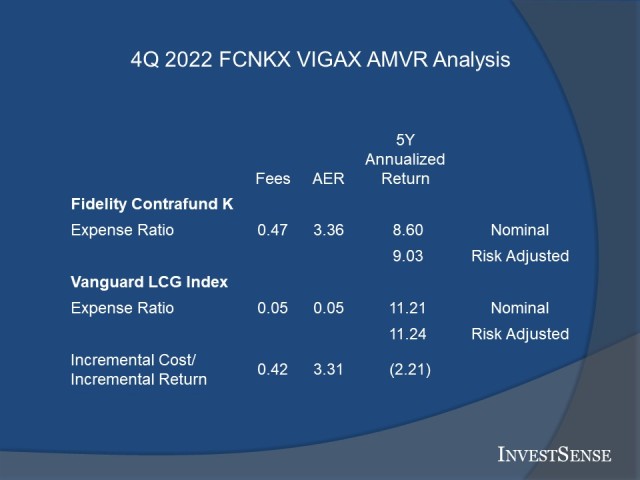

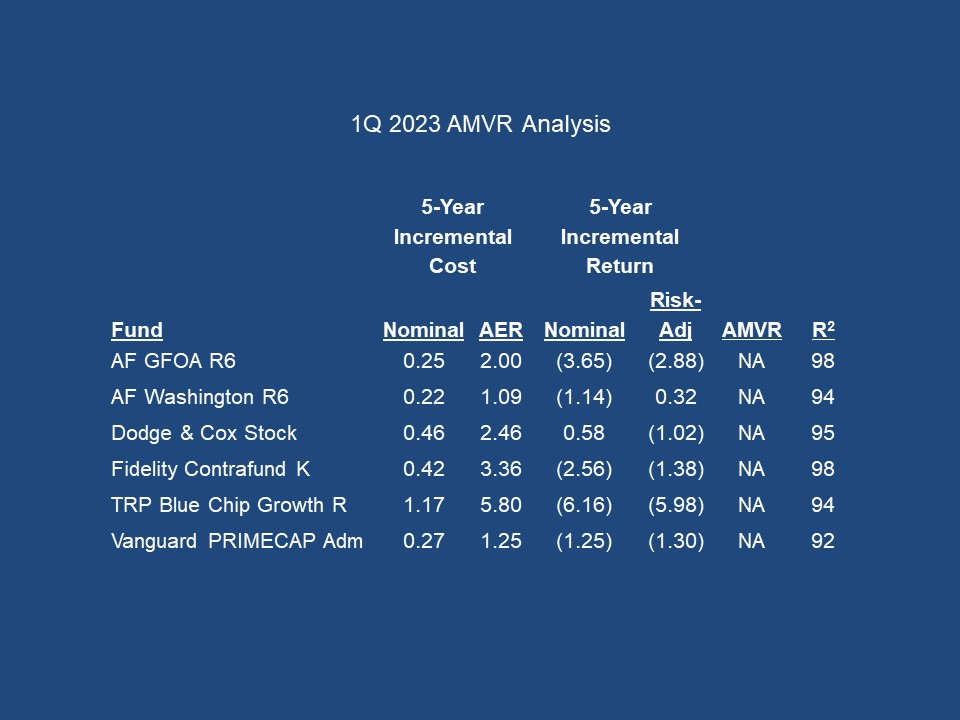

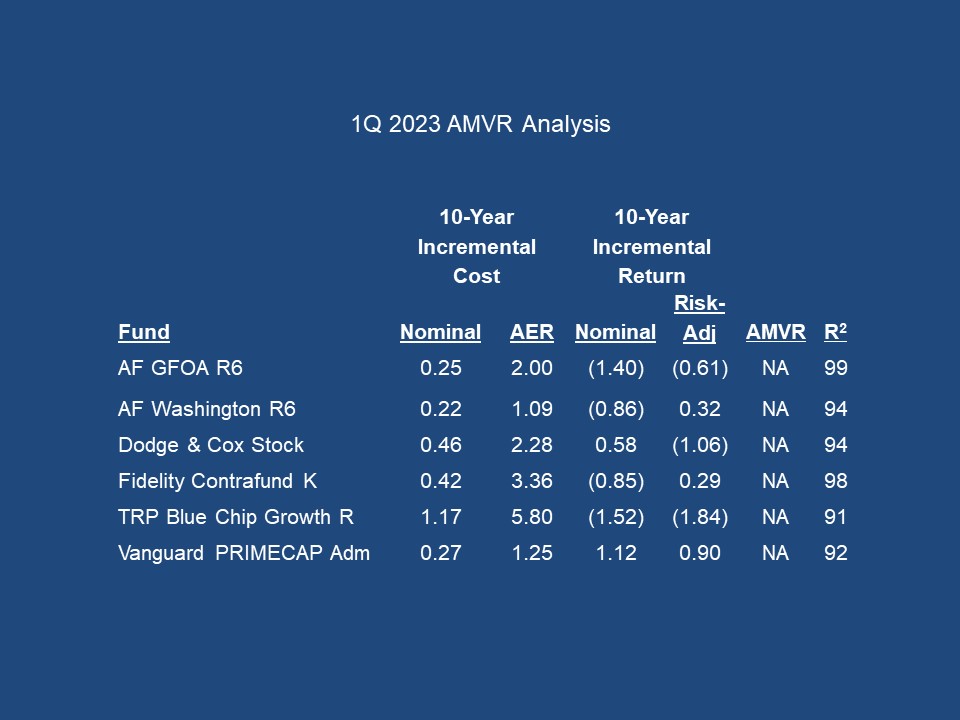

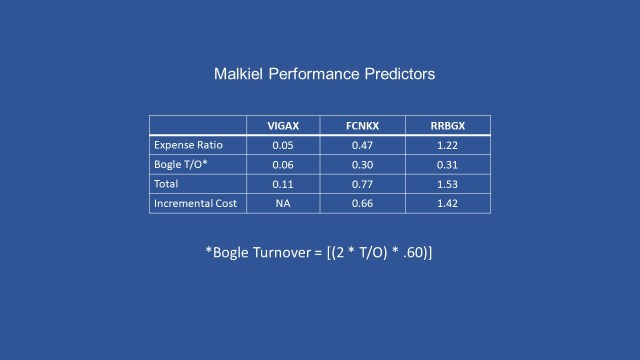

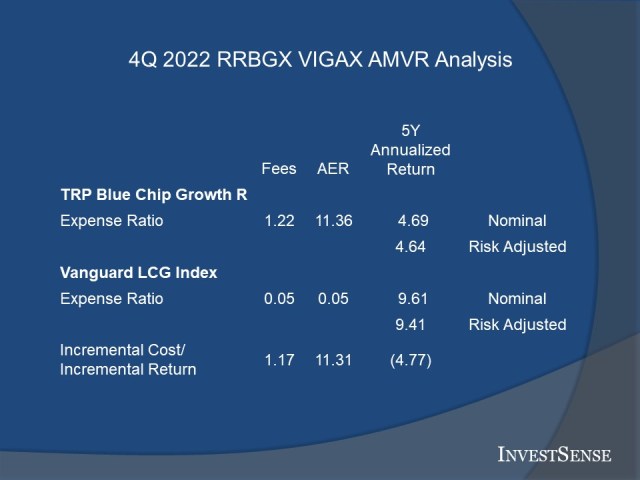

As both the Department of Labor and the federal General Accountability Office have pointed out, each additional one percent in fees and expenses in a product reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent over a twenty-year period.1 Riders often cost an additional one percent or more of the annuity’s accumulated value. When combined with an annuity’s other annual costs, it is easy to see how over half of an annuity owner’s end-return can be lost in an annuity’s annual fees (3 times 17).

Annuities, Plan Sponsors, and the Fiduciary Liability Gauntlet

A CEO invited me to lunch recently to discuss the potential liability issues of offering annuities within his company’s 401(k) plan. Before lunch was over, two other executives sitting nearby came by our table and asked me to call them to discuss the issue.

Full disclosure – I do not like annuities. Never have, never will. My strong dislike of annuities is due primarily to my experience with the annuity industry during my time as a plaintiff’s attorney . I was involved in litigating some medical malpractice and wrongful death cases. When a personal injury case potentially involves significant monetary damages, the defendant’s insurer typically suggests a structured settlement involving an annuity.

As a plaintiff’s attorney, if the defense offers to settle for a million dollars, the plaintiff’s attorney has to ensure that the plaintiff is actually going to receive a settlement with a present value of a million dollars. Failure to do so will typically result in a malpractice claim against the attorney.

The courts have consistently held that the present value of a settlement involving an annuity is the actual purchase price of the annuity, the out-of-pocket costs the insurance company will incur in purchasing the annuity being considered. However, many insurance companies refuse to disclose the actual purchase price of the annuity since it is typically well below the agreed upon settlement price, ensuring a windfall for the annuity issuer. Fortunately, the plaintiff can avoid such dishonesty by asking the court to approve of the creation of a “qualified settlement fund, ” (QSF) into which the settlement proceeds are paid so that the plaintiff can purchase an annuity at a fair price and avoid full and immediate taxation of the settlement proceeds.

I see a similar situation potentially developing in the annuity industry’s current campaign to offer more annuity products within pension plans. As a fiduciary risk management counsel, my job is to explain the potential fiduciary liability pitfalls to plan sponsors in order to avoid unnecessary liability exposure. In my presentations, I currently focus on four areas: (1) a plan sponsor’s duty to personally investigate and evaluate each investment option within a plan, (2) ERISA Section 404(c)’s “adequate information to make an informed decision” requirement, (3) a plan sponsor’s fiduciary duty, which includes a duty to disclose all material information to plan participants, and (4) a plan sponsor’s fiduciary prudence duties under ERISA Section 404(a).

ERISA Section 404(a)’s “Knew or Should Have Known” Standard

Section 404(a) sets out a plan sponsor’s fiduciary duty of prudence:

a fiduciary shall discharge his duties with respect to a plan …with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent man acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims;…2

In determining whether a trustee has breached his duties, the court examines both the merits of the challenged transaction(s) and the thoroughness of the fiduciary’s investigation into the merits of the transaction(s).3

A fiduciary’s independent investigation of the merits of a particular investment is at the heart of the prudent person standard. (citing Donovan v. Cunningham, 716 F.2d 1455, 1467 (5th Cir. 1983); Donovan v. Bierwirth, 538 F.Supp. 463, 470 (E.D.N.Y.1981). The determination of whether an investment was objectively imprudent is made on the basis of what the trustee knew or should have known; and the latter necessarily involves consideration of what facts would have come to his/her attention had he/she fully complied with their duty to investigate and evaluate all plan investment options. It is the imprudent investment rather than the failure to investigate and evaluate that is the basis of suit; breach of the latter duty is merely evidence bearing upon breach of the former, tending to show that the trustee should have known more than he knew.# (emphasis added)4

While courts recognize, even encourage, the use of third parties in the fiduciary’s investigation and evaluation process, the courts have consistently warned that plan sponsors and other plan fiduciaries may not blindly rely on such experts, especially “experts” that are commission salespersons.

Blind reliance on a broker whole livelihood was derived from the commissions he was able to garner is the antithesis [of a fiduciary’s duty to conduct an] independent investigation”5

“The failure to make an independent investigation and evaluation of a potential plan investment is a breach of fiduciary duty.”6

Sponsors must conduct a thorough and objective investigation and evaluation in selecting investment products for a plan. Fiduciary prudence focuses on the process used by a plan sponsor in investigating and evaluating the investment products chosen for a plan, not the eventual performance of the product. In assessing the process used by a plan sponsor, the court evaluate prudence in terms of both procedural and substantive prudence.

Procedural prudence focuses on whether the fiduciary utilized appropriate methods to investigate and evaluate the merits of a particular investment. Substantive prudence focuses on whether the fiduciary took the information from the investigation and made the same decision that a prudent fiduciary would have made.

The Tatum v. RJR Pension Inv. Committee decision7 provides an excellent analysis of various types of fiduciary prudence – objective prudence, procedural prudence, and subjective prudence. It also involves the analysis of an annuity, although in a defined benefit plan context.

The court first addressed the concept of “objective prudence, stating that

A decision is objectively prudent is a hypothetical prudent fiduciary would have the same decision.8 (emphasis added)

I have deliberately added emphasis to the word “would,” as it was a pivotal issue in the court’s decision. The plan sponsor had argued, and the lower court had accepted their argument, that it was sufficient to show that a hypothetical prudent fiduciary “could” have made the same decision.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected that argument, stating that the chosen word with regard to the applicable fiduciary prudence standard was more than just a matter of semantics.

ERISA requires fiduciaries to employ “appropriate methods to investigate the merits of the investment and to structure the investment” as well as to “engage in a reasoned decision-making process, consistent with that of a `prudent man acting in [a] like capacity.'”9

In other words, although the duty of procedural prudence requires more than “a pure heart and an empty head,” courts have readily determined that fiduciaries who act reasonably — i.e., who appropriately investigate the merits of an investment decision prior to acting — easily clear this bar.10

[I]n matters of causation, when a beneficiary has succeeded in proving that the trustee has committed a breach of trust and that a related loss has occurred, the burden shifts to the trustee to prove that the loss would have occurred in the absence of the breach.” (citing Restatement (Third) of Trusts § 100, cmt. f (2012))11

As the Supreme Court has explained, the distinction between “would” and “could” is both real and legally significant….[C]ould” describes what is merely possible, while “would” describes what is probable.12

The “would have” standard is, of course, more difficult for a defendant-fiduciary to satisfy. And that is the intended result. “Courts do not take kindly to arguments by fiduciaries who have breached their obligations that, if they had not done this, everything would have been the same.” …We would diminish ERISA’s enforcement provision to an empty shell if we permitted a breaching fiduciary to escape liability by showing nothing more than the mere possibility that a prudent fiduciary “could have” made the same decision.13 (cites omitted

The court then went on to address the issue of objective and substantive prudence:

a decision is “objectively prudent” if “a hypothetical prudent fiduciary would have made the same decision anyway.”14 (emphasis added)

As mentioned earlier, substantive prudence focuses on the plan sponsor’s consideration of the facts uncovered in its investigations and whether the plan sponsor properly factored in such information and made a legally proper decision.

Other courts have identified key factors that plan sponsors must address in considering annuities.

A fiduciary must consider any potential conflict of interest, such as a potential reversion of plan assets, and structure its investigation accordingly.15

Just as with experts’ advice, blind reliance on credit or other ratings is inconsistent with fiduciary standards.16

With regard to the potential reversion of plan assets involving annuities or the receipt of same by third parties, such as other annuity owners of the insurance comapny, I would (and have) argued that the fact that reversion to the annuity issuer is especially egregious and constitutes a breach of a plan sponsor’s fiduciary duties of both loyalty and prudence based upon the fact that such a reversion would constitute a windfall for the annuity issuer or a related party, the annuity issuer’s other annuity owners, at the annuity owner’s expense. Equity law is a component of fiduciary law, and “equity abhors a windfall.”

The court concluded by emphasizing that the controlling criteria was whether an annuity under consideration was in the best interest of the plan participants and their beneficiaries. The question will be whether plan sponsors can obtain the necessary information to independently evaluate and verify the accuracy of such information, as well as the ability to interpret the implications of the annuity information they can uncover.

For example, will plan sponsors be able to determine whether plan participants will even be able to breakeven on a particular annuity, especially if the annuity issuer retains the right to reset the terms? Will plan sponsors be able to understand the difference between an ordinary annuity and an annuity due and provide plan participants with the information on the financial implications of each, e.g., breakeven analysis?

ERISA’s “Adequate Information to Make an Informed Decision” Requirement

Plan sponsors typically try to qualify as a 404(c) plan in order to receive immunity from liability for the ultimate performance of the plan participants’ investment choices. Qualification for such protection requires compliance with approximately twenty requirements. As a result, many plan sponsors mistakenly believe they are in compliance with 404(c) when they actually are not.

An “ERISA section 404(c) Plan” is an individual account plan described in section 3(34) of the Act that:

(i) Provides an opportunity for a participant or beneficiary to exercise control over assets in his individual account (see paragraph (b)(2) of this section); and

(ii) Provides a participant or beneficiary an opportunity to choose, from a broad range of investment alternatives, the manner in which some or all of the assets in his account are invested (see paragraph (b)(3) of this section).

(2) Opportunity to exercise control.

(i) a plan provides a participant or beneficiary an opportunity to exercise control over assets in his account only if:

(B) The participant or beneficiary is provided or has the opportunity to obtain sufficient information to make informed investment decisions with regard to investment alternatives available under the plan, and incidents of ownership appurtenant to such investments. For purposes of this paragraph, a participant or beneficiary will be considered to have sufficient information if the participant or beneficiary is provided by an identified plan fiduciary (or a person or persons designated by the plan fiduciary to act on his behalf)…17

As pointed out earlier, the financial services industry, in particular the insurance/annuity industry, are not known for their support of transparency and/or full disclosure. Transparency and full disclosure are the financial services kryptonite. Anytime there is any mention of a true fiduciary standard for the industry, the industry’s lobbyists grab their checkbooks and head toward Capitol Hill, as the financial services industry knows that few, if any, of its products would comply with a true fiduciary standard. They just hope that plan sponsors and consumers never realize that fact.

Annuities present a number of challenges for plan sponsors hoping to qualify for 404(c) protections. Annuities are extremely complex, and deliberately so. There is a saying within the annuity industry, “annuities are sold, not bought.” Anyone who truly understands guaranteed lifetime income annuities would never consider buying one, especially when viable, cost-efficient alternatives are readily available that do not require the investment owner to agree to the unnecessarily harsh terms required by annuity companies.

Annuities have been described as a bond wrapped in an expensive insurance wrapper. The primary issue with commercial annuities is the associated costs, both in terms of monetary costs and opportunity costs in terms of other financial goals, such as estate planning. Annuity advocates will often turn to their “guaranteed income for life” and “no loss” mantras. Annuity opponents will counter with their “at what cost” mantra and the viable cost-efficient alternatives available. Financial service publications have run articles explaining how financial advisers can even help their customers create viable, cost-efficient annuity substitutes.

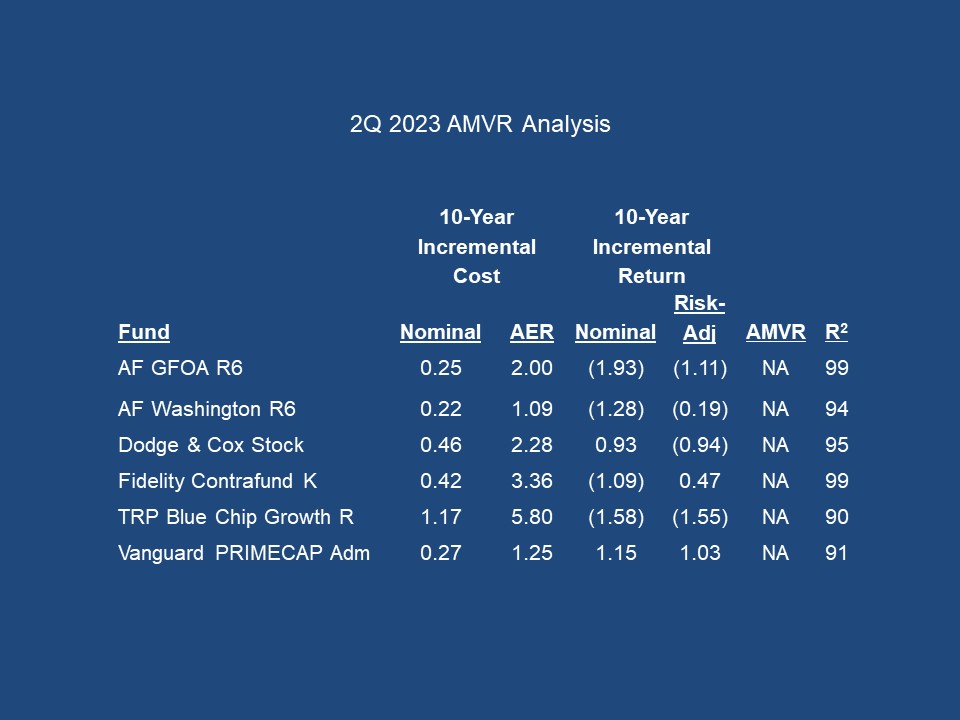

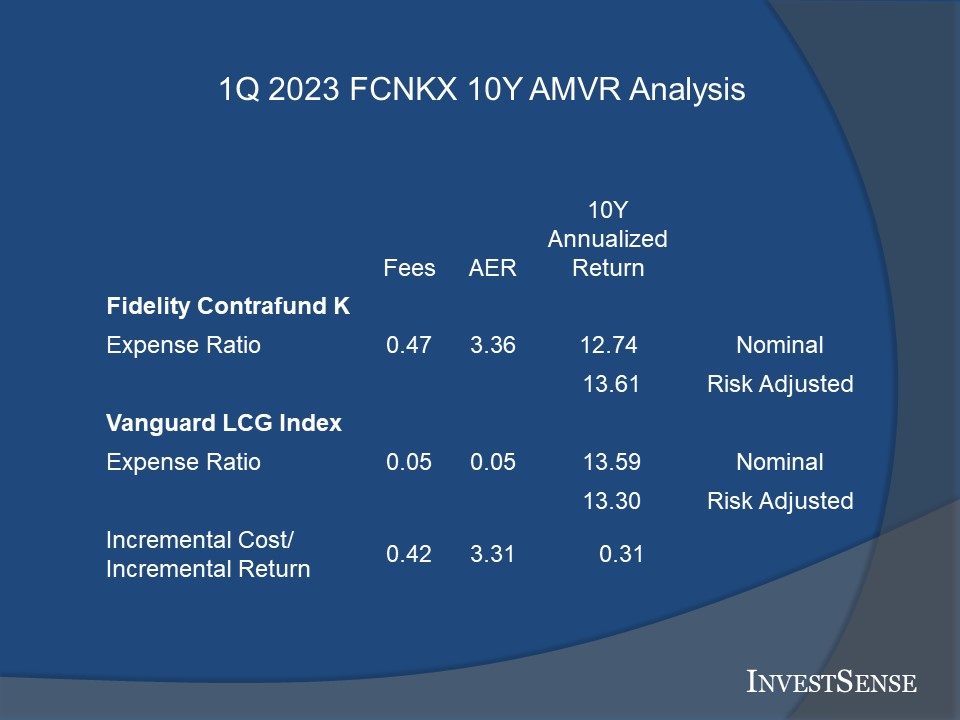

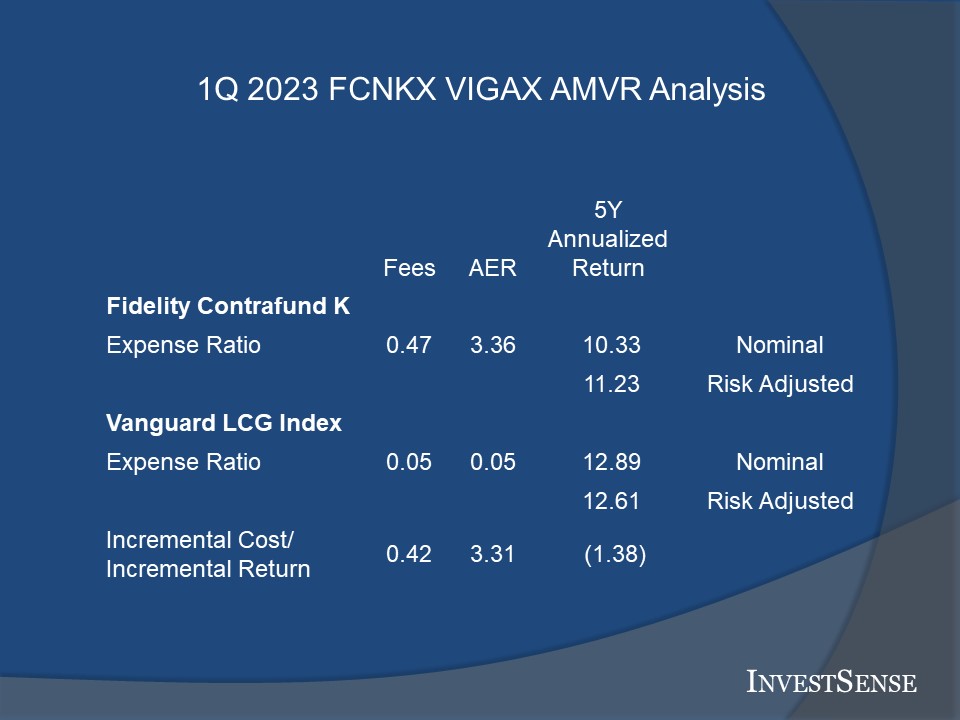

With annual fees/spreads often in the range of two percent or more, plan sponsors should remember the findings of both the Department of Labor and the General Accountability Office that each additional one percent in fees reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately seventeen percent over a twenty-year period.18 Add a rider charging an additional annual fee of one percent and the investor now faces a reduction of over half of their end-return (3 times 17). Hard to see how a plan sponsor can explain the prudence of including annuities reducing end-returns by one-third to one-half, or more, over more cost-efficient, investor friendly alternatives.

There is no requirement that a 401(k) plan qualify as a 404(c) plan. However, the inability to qualify as a 404(c) plan potentially raises a number of fiduciary prudence and loyalty questions. Given the annuity industry’s unwillingness to provide material information about their products, how can a plan sponsor perform the legally required independent and objective investigation and evaluation required by ERISA? Likewise, how will a plan sponsor provide the ongoing monitoring of each annuity and annuity related product offered within a plan?

If a plan offers annuities which allow the annuity provider to reset or otherwise change the terms of the annuity to protect and benefit the annuity issuer, what are the options and potential consequences for both plan participants and plan sponsors? An even more basic question for plan sponsons is how do they determine whether sufficient information has been, and will continue to be, provided. Remember, plan sponsors that chose to blindly rely on third party information face an unforgiving legal system. These are just some samples of legal liability issues that plan sponsors should consider before choosing to include annuity options within a 403(k) or 403(b) plan. Unfortunately, annuity advisers generally try to avoid addressing such potential legal liability issues. “Not our job” and “we are not acting as fiduciaries” is their common response.

Annuities and ERISA Requirements

ERISA does not expressly require plan sponsors to offer annuities, in any form, within a 401(k) or 403(b) plan. It’s just that simple.

In fact, ERISA does not expressly require a plan to offer any specific type of investment product. ERISA 404(a) only requires that each investment option within a plan be prudent. SCOTUS resolved that issue in the Hughes v. Northwestern University19 case.

So, the obvious question is why, given the various hurdles and the potential fiduciary liability traps inherent with annuities, would a plan sponsor voluntarily expose themselves to unnecessary fiduciary liability exposure? After all, a plan participant wanting to purchase an annuity could easily do so outside of the plan, without creating any potential liability issues for the plan sponsor.

Plan sponsors often try to justify the inclusion of an otherwise legally imprudent investment option based upon a desire to provide plan participants with “choices.” A legally imprudent investment option never has been, and never will be, a legally valid investment “choice.” The fact that a plan sponsor would even include a legally imprudent investment, e.g., a cost-inefficient actively managed mutual fund, simply serves as a red flag for regulators with regard to the overall prudence of the plan’s selection process.

The good news is that it is relatively simple to design and maintain an cost-effective and ERISA compliant 401(k) or 403(b) plan. The bad news is that far too few plan sponsors do so.

Going Forward

[A] fiduciary satisfies ERISA’s obligations if, based upon what it learns in its investigation, it selects an annuity provider it “reasonably concludes best to promote the interests of [the plan’s] participants and beneficiaries.”20

Based on the information presented herein and a plan sponsor’s fiduciary duties of prudence and loyalty, key questions in future 401(k)/403(b) litigation involving the inclusion of annuities and/or annuity related products in plans could/should include

(1) Would a prudent plan sponsor decide to include an annuity as an investment option within a plan when that annuity requires the annuity owner to surrender both the investment contract and the accumulated value within the annuity without any guarantee of a commensurate return?

(2) Would a prudent plan sponsor decide to include an annuity as an investment option within a plan when the terms of the annuity contract legitimately raises questions as to the odds of the annuity owner ever breaking even and, if so, how long it would take?

(3) Would a prudent plan sponsor decide to include an annuity as an investment option within a plan if the annuity issuer reserves the right to reset the terms and guarantees within the annuity and impact the results of questions (1) and (2).

(4) Would a prudent plan sponsor decide to include an annuity as an investment option within a plan if the fees were so excessive as to potentially reduce an annuity owner’s end-return by one-third or more?

(5) Under the SECURE Act, plans sponsors are protected from liability in the event that annuities offered within their plan are unable to honor their financial commitments under their contracts. Yet, plan participants who purchase such annuities within a plan are not protected against loss in such circumstances. Given the obvious inequity in the event of such a situation, where plan sponsors are protected but plan participants are not, would the courts consider your decision to offer such annuities in your plan to be a breach of your fiduciary duties of prudence and/or loyalty?

If, as many ERISA attorneys expect, SCOTUS rules that the burden of proof as to causation shifts to the plan sponsor once the plan participants prove a fiduciary breach and resulting loss, these are questions that plan sponsors are going to be forced to face in future 401(k)/403(b) litigation. The answers, and resulting liability, would appear to be readily apparent.

While most people would agree that the concept of “guaranteed lifetime income” is highly desirable, from a legal and fiduciary liability perspective, the concept always needs to be balanced and conditioned on the question of “at what cost?” As mentioned earlier, in this case, “costs” that would need to be considered are not only financial costs, but also opportunity costs, such as the impact on estate planning and other types of financial planning.

Many would argue that the various costs and concessions associated with annuities, in any form, are simply not worth the “costs,” especially when other equally effective and more cost-efficient alternatives and strategies are available, such as dividends and bonds, e.g., Treasury and corporate, and laddering such bonds. Corporate trust departments often rely on the dividends on utility stocks for guaranteed income. Trusts departments and some fiduciaries have been known to create their own annuities using a combination of bonds, life insurance, and index mutual funds.

I am on record as predicting that the defined contribution arena is going to undergo a significant change in the next 12-18 months, especially in the area of litigation, as a result of the pending decisions in the Cunningham v. Cornell University and the Retirement Security Rule cases. A key question in both cases is which party carries the burden of proof on the issue of causation in defined contribution litigation.

I believe that both cases will result in the burden of proof on the issue of causation in 401(k) /403(b) litigation being shifted to the plans since they alone have access to all of the relevant information. As a result, I believe that there will be a significant increase in the number of cases litigated, both between plans/plan participants and plans/plan advisers, due largely to the fact that most plans cannot and will not be able to successfully meet the burden of proving that their investment selections did not play a role in causing losses sustained by plan participants.

As I explain to my fiduciary risk management clients, there are some well-recognized fiduciary standards that should be followed in evaluating and selecting investments offering guaranteed income. Exposing a plan to unnecessary fiduciary liability exposure is one of those standards, with my corollary for fiduciaries is simply “annuities – Not legally required, so why go there? Don’t go there.”

Previous posts on the unnecessary liability exposure that annuities create for defined contribution plans can be found here, here, and here

Notes

1. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (“DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study”).

2. 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404(a)-1; 29 U.S.C. § 1104(a).

3. The failure to make any independent investigation and evaluation of a potential plan investment is a breach of fiduciary obligations. Fink v. National Savs. & Trust Co., 772 F.2d 951, 957 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (Fink), In re Enron Corp. Securities, Derivative “ERISA“, 284 F.Supp.2d 511, 549-550, Donovan v. Cunningham, 716 F.2d at 1467.52

4. Fink, 962. (Scalia dissent)

5. Liss v. Smith, 991 F. Supp. 278, 299.

6. United States v. Mason Tenders Dist. Council of Greater NY,, 909 F. Supp 882, 887 (S.D.N.Y. 1995)

7. Tatum v. RJR Pension Inv. Committee, 761 F.3d 346 (4th Cir. 2014). (Tatum).

8. Tatum, 363.

9. Tatum, 358.

10. Tatum, 363.

11. Bussian v. RJR Nabisco, Inc., 223 F.2d 286, 300 (5th Cir. 2000). (Bussian)

12. Tatum, 365.

13. Tatum, 365.

14. Tatum, 363; Bussian, 300 (5th Cir. 2000).

15. Bussian, 300.

16. Bussian, 301.

17. 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404(c); 29 U.S.C. § 1104(c).

18. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study).

19. Hughes v. Northwestern University, 142 S. Ct. 737, 211 L. Ed. 2d 558 (2022

20. DOL Interpretitive Bulletin 95-1.

Resources

Collins, P.J., Lam, H., & Stampfi, J. (2009) “Equity indexed annuities: Downside protection, but at what cost?” Journal of Financial Planning, 22, 48-57.

FINRA Investor Insights (2022) “The Complicated Risks and Rewards of Indexed Annuties” The Complicated Risks and Rewards of Indexed Annuities | FINRA.org

FINRA Investor Alert (2003) “Variable Annuities: Beyond the Hard Sell”

Frank, L., Mitchell, J. & Pfau, W. “Lifetime Expected Income Breakeven Comparison Between SPIAs and Managed Portfolios,” Journal of Financial Planning, April 2014, 38-47.

Katt, P. (November 2006) “The Good, Bad, and Ugly of Annuities,” AAII Journal, 34-39.

Lewis, W. Chris. 2005. “A Return-Risk Evaluation of an Indexed Annuity Investment.” Journal of Wealth Management 7, 4.

McCann, C. & Luo, D. (2006). “An Overview of Equity-Indexed Annuities.” Working Paper, Securities Litigation and Consulting Group.

Milevsky, M. & Posner, S. “The Titanic Option: Valuation of the Guaranteed Minimum Death Benefit in Variable Annuities and Mutual Funds,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2009), 91-126.

Olson, J. “Index Annuities: Looking Under the Hood.” Journal of Financial Services Professionals. 65-73 (November 2017),

Reichenstein, W. “Financial analysis of equity-indexed annuities.” Financial Services Review, 18 (2009) 291-311.

Reichenstein, W. (2011), “Can annuities offer competitive returns?” Journal of Financial Planning, 24, 36.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2008) “Investor Alerts and Bulletins: Indexed Annuties,”SEC.gov | Updated Investor Bulletin: Indexed Annuities

Sharpe, W.F. (1991) “The arithmetic of active management,” Financial Analysts Journal, 47, 7-9.

Terry, A. & Elder, E. (2015) “A further examination of equity-indexed annuities,” 24, 411-428.

Copyright InvestSense, LLC 2023, 2025. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is neither designed nor intended to provide personal legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.