James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP EmeritusTM, AWMA®

Looking at the ERISA litigation landscape for 2025, I think there are three clear-cut cases that may shape the future of ERISA litigation and ERISA itself: the ongoing litigation in the Fifth Circuit over the DOL’s Retirement Security Rule (Rule)1, the Sixth Circuit’s Parker-Hannifin case (Hannifin)2, and the Cunningham v. Cornell University (Cornell)3 case, which is scheduled for oral arguments before SCOTUS on January 22, 2025. I believe SCOTUS’ decision in the Cornell case will likely impact the ultimate disposition of both of the other two cases.

I have already posted my opinion on the 5th Circuit’s actions in connection with the Retirement Security Rule. I believe District Court Judge Barbara Lynn’s decision upholding and her supporting rationale was spot on. The dissenting opinion filed by Fifth Circuit Chief Judge Stewart in connection with the Court’s decision to stay the effectiveness of the Rule was equally on point.4

There has been no movement in the case since the stay was issued in July, effectively leaving plan participants vulnerable to the annuity industry’s abusive marketing tactics that necessitated the creation of the Rule in the first place. As Judge Lynn pointed out in her decision5upholding the Rule, FIAs involve investor/consumer interest issues that clearly work to the benefit of the FIA issuer at the expense of the annuity owner.

[I]nsurers generally reserve the right to change participation rates, interest caps, and fees, FIAs can effectively transfer investment risks from insurers to investors….You can lose money buying indexed annuities….even with a specified minimum value from the insurance company, it can take several years for an investment in an indexed annuity to breakeven.6

Such uncertainty also effectively prevents plan sponsors, from complying with ERISA’s requirement that they conduct independent and objective fiduciary prudence investigations and evaluations on each investment offered within a plan.

As for the Parker-Hannifin case, there are several ERISA related issues involved in the case, including pleading issues, including who has the burden of proof on the issue of causation of damages. The importance of the case and its issues is reflected in the number of amicus briefs that have already been filed, most notably the amicus brief of the U.S. Solicitor General.

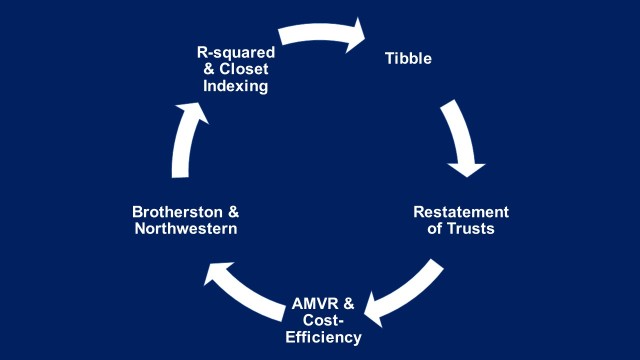

As a fiduciary risk management counsel, one of my services is to help plan sponsors understand the importance of developing a sound, legally compliant fiduciary process for a plan to follow in selecting and monitoring a plan’s investment options. To make the technical complexities of ERISA and fiduciary compliance simpler to understand I created what I call the Fiduciary Prudence CircleTM (Circle). In my practice, I recommend that my clients use the Circle as the foundation for developing a sound fiduciary prudence process that will withstand judicial scrutiny.

Tibble v. Edison International7 is a cornerstone decision in developing a prudent fiduciary process. Courts often cite Tibble for the fact that the Supreme Court (SCOTUS) officially recognized the Restatement of Trusts (Restatement) as a legitimate resource in resolving questions about fiduciary prudence. The Restatement of Trusts is essentially a codification of the common law of trusts. As SCOTUS noted

We have often noted that an ERISA fiduciary’s duty is ‘derived from the common law of trusts.’ In determining the contours of an ERISA fiduciary’s duty, courts often must look to the law of trusts.(citations omitted)8

So, the obvious question would appear to be – “What standards does the Restatement establish with regards to fiduciary Prudence?”

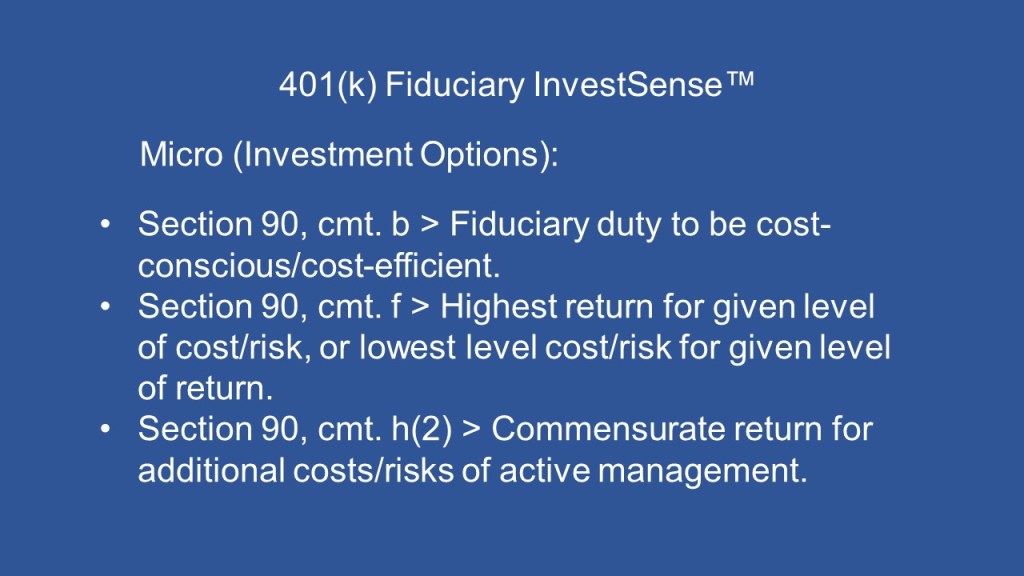

I believe that that three comments in Section 90, aka the Prudent Investor Rule, merit special attention for plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries – comments b, f, and h(2).

Comments b and f focus on cost-efficiency. In 2015, the DOL issued Interpretive Bulletin 15-019(IB 15-01). IB 15-01 reinstated earlier language from Interpretive Bulletin 94-14, specifically the following:

Consistent with fiduciaries’ obligations to choose economically superior investments….[P]lan fiduciaries should consider factors that potentially influence risk and return.5 (emphasis added)10

[B]ecause every investment necessarily causes a plan to forgo other investment opportunities, an investment will not be prudent if it would provide a plan with a lower expected rate of return than available alternative investments with commensurate degrees of risk or is riskier than alternative available investments with commensurate rates of return.11

Sure sounds a lot like comment f from Section 90 of the Restatement. Sure sounds like further support for the use of cost-benefit analysis in evaluating the fiduciary prudence of the decisions of plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries. Sure sounds like further support for the Active Management Value Ratio metric, which measures the cost-efficiency of an actively managed mutual fund relative to a comparable index fund.

Comment h(2)12focuses on the concept of commensurate return, or return relative to the additional risk and cost incurred by an investor. This is further support for simple cost-benefit analysis as part of any fiduciary prudence process. Cost-benefit analysis is a common practice in the business world in evaluating the viability of a project. However, the financial services industry and the annuity industry have essentially rejected the use of cost-benefit analysis. I would suggest that there is a good reason for such rejection.

That reason may become even more significant if SCOTUS rules that plan sponsors carry the burden of proof on the issue of causation, which I believe is exactly how SCOTUS will rule in Cunningham v. Cornell, based on not only the Solicitor General’s most recent amicus brief to the court, but also on the amicus brief that the Solicitor General filed in connection with the Brotherston case.13 I belleve that earlier amicus brief, combined with the First Circuit ‘s Brotherston decision and the Solicitor General’s amicus brief provided an outstanding analysis of why the plan sponsor, both logically and by necessity, must be the party responsible for carrying the burden of proof on the issue of causation.

Both the First Circuit and the Solicitor General referenced Section 100 of the Restatement in their arguments. Section 100, comment (b) endorses the use of index funds as comparators in assessing the prudence of actively managed funds in plans, while Section 100 comment (f) addresses the allocation of the burden of proof.

When a plaintiff brings suit against a [plan sponsor]for breach of trust, the plaintiff generally bears the burden of proof . The general rule, however, is moderated in order to take account of the [plan sponsor’s]duties of disclosure …as well as the [plan sponsor’s] (often, unique access to information about the [plan] and its activities, and also to encourage the plan sponsor’s compliance with applicable fiduciary duties.15

That is what is so puzzling about the reluctance of some courts to follow the Restatement and shift the burden of proof to the party with the necessary information once the plaintiff has met its duty to plausibly plead its claims and establish a resulting loss from such fiduciary breaches. Since SCOTUS has already legitimized the Restatement as a resource in cases involving fiduciary cases, it would seem justifiable that the Court will reference Section f in ruling that the burden of proof as to causation once the plaintiff plausibly pleads a breach of fiduciary duty and provides evidence of the resulting loss. Common sense and common law.

In Brotherston, the First Circuit recognized the importance of Section 100 by stating that

[T]he Restatement specifically identifies as an appropriate comparator for loss calculation purpose ‘return rates of one or more …suitable index mutual funds or market indexes (with such adjustments as may be appropriate.16 (citing Section 100, comment b(1)

ERISA itself is not so specific. Rather it states that a breaching fiduciary shall be liable to the plan for ‘any losses to the plan resulting from each such breach. Certainly the text is broad enough to accommodate the total return recognized in the Restatement. Behind the text, too, stands Congress’ clear intent ‘to provide the courts with broad remedies for redressing the interests of participants and beneficiaries when they have been adversely affected by breaches of fiduciary duty.17

[T]he Supreme Court has made clear that whatever the overall balance the common law might have struck between the protection and beneficiaries, ERISA’s adoption reflected ‘Congress'[s] desire to offer employees enhanced protection for their benefits….In other words, Congress sought to offer beneficiaries, not fiduciaries, more protection that they had at common law, albeit while still paying heed to the counterproductive effects of complexity and litigation risk.18

The Solicitor General also filed an amicus brief in connection with SCOTUS’ consideration on whether to grant certiorari and hear Putnam LLC’s appeal of the First Circuit’s Brotherston decision. While SCOTUS ultimately decided not to review the First Circuit’s, due largely to the fact that it was an interlocutory appeal, as the trial was technically still ongoing, the Solicitor General cited Section 100, comment f, on the burden of proof issue, stating that

Under trust law, ‘when a beneficiary has succeeded in proving that the trustee has committed a breach of trust and that a related loss has occurred, the burden of proof shifts to the [fiduciary] to prove that the loss would have occurred in the absence of the breach.19

I would, and have, argued, that the concept of incorporating the simple arithmetic of cost-benefit analysis, in the form of the Active Management Value Ratio metric, accomplishes the stated goal while complying with any counterproductive effects other than establishing a fiduciary’s breach of duty. Furthermore, cost-benefit analysis and, in the case of annuities, breakeven analysis, factoring in both present value and mortality risk, will more often than not prevent a plan sponsor from carrying their burden of proof on the issue of causation, assuming the plan participants carry their preliminary burden of both breach and resulting loss.

The Supreme Court has time and again adopted ordinary trust law principles to construe ERISA in the absence of explicit textual direction.20

The First Circuit also noted many of the same issues and concerns addressed in the Solicitor General’s amicus brief, including “Congress’ indicated desire to ‘offer employees enhanced protection of their benefits,” and “Congress’ intent to offer [plan participants], not plan sponsors, more protection than they had a common law.

The Supreme Court has time and again adopted ordinary trust law principles to construe ERISA in the absence of explicit textual direction.21

The Solicitor General filed an excellent amicus brief with the SCOTUS, also referencing Section 100, stating that

[A] beneficiary has the burden of showing only ” a prima facie case,’ at which point ‘the burden of contradicting it or showing a defense will shift to the [plan sponsor.’22

Applying trust law’s burden shifting framework to ERISA fiduciary -breach claims also furthers ERISA’s purposes. In trust law, burden shifting rests on the view that ‘as between innocent [plan participants] and a defaulting [plan sponsor], the latter should bear the risk of uncertainty as to the consequences of its breach of duty.23

ERISA reflects congressional intent to provide more protections than trust law. Applying trust law’s burden shifting framework, which can serve to deter ERISA fiduciaries from engaging in wrongful conduct, thus advances ERISA’s protective purposes. By contrast, declining to apply trust-law’s burden-shifting framework could create significant barriers to recovery for conceded fiduciary breaches.24

The fiduciary is in the best position to provide information about how it would have made investment decisions in light of the objectives of a particular plan and the characteristics of plan participants. Indeed, this Court recognized in Schaffer that ii is appropriate in some circumstances to shift the burden to establish ‘facts particularly within the knowledge’ of one party.25

[T]he ‘common sense concern’ underscoring a burden-shifting regime is that ‘it makes little sense to have the plaintiff hazard a guess as to what the [plan sponsor would have done had it not breached its duty.26

The First Circuit’s Brotherston opinion set out many of the same concerns ands rationales as the Solicitor General’s amicus brief.

This from the Solicitor General’s 2024 amicus brief:

Courts should generally not depart from the usual practice under [the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure](F.R.C.P) on the basis of perceived policy concerns. In any event, a district court has various tools to screen out implausible claims. To survive a motion to dismiss under F.R.CP. 12(b)(6), a compliant must plead “enough facts to state a claim for relief that is plausible on its face. (citing Bell Atl. Corp v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007); Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009)(emphasis added)27…[A]n inference pressed by the plaintiff is not plausible if the facts he points to are precisely the result one would expect from lawful conduct in which the defendant is known to have engaged.27

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure establish the rules of pleading in the federal (and generally all) courts. Under F.R.C.P. 8,28 plaintiffs are generally held to “notice pleading, simply providing enough information to apprise the defendant of the nature of the plaintiff’s claims. However F.R.C.P Rule 9, “Pleading Special Matters,” Subsection (b), “Fraud or Mistake, Conditions of the Mind,” states that “Malice, intent knowledge and other conditions of a person’s mind may be alleged generally.29 I maintain that since plan participants are generally not aware of the deliberative process used by a plan’s investment committee, courts demanding specific allegations as to an investment committee’s processes, if any, are trying to force plan participants to do more than they are required to do under the F.R.C.P,

The Solicitor General addressed such concerns as well:

[P]etitioners’s factual allegations sufficed to plausibly allege that the challenged transactions for recordkeeping services were not obviously reasonable.30

As a practical matter, moreover, it is not clear what additional facts petitioners could have alleged that would have satisfied the court of appeals, without the benefit of discovery….[P]articipants would likely require discovery into additional facts in the fiduciaries’ possession-such as the terms of of the contract, the range of contracted services, and performance metrics that justify the fees charged-to ascertain the quality and full extent of the services provided.31

Any yet, how many times have we seen cases prematurely dismissed citing plan participants’ failure to provide such information, involving the mental processes of the plan sponsor and/or plan investment committee, while denying plan participants with the opportunity to have of the necessary discovery referenced by the Solicitor General.

The Solicitor General concluded her amicus brief with a simple sentence – “A plaintiff’s claims should not be prematurely dismissed due to the absence of facts that it cannot obtain.”32 Yet the injustice continues to happen every day, an injustice that effectively denies over half of America’s employees the rights and protections guaranteed to them under ERISA.

It should be noted that an increasing number of courts have addressed the fact that some courts are attempting to force upon plan participants an inequitable and impossible burden, the burden of proof with regard to causation, without allowing the participants the discovery necessary to carry such burden. Two well known jurists which have recently addressed the burden of proof as to causation and resulting inequitable premature dismissal of meritorious claims are Sixth Circuit Chief Judge Sutton and District Court Judge Sidney Stein of the Southern District of New York, more commonly known as Wall Street’s federal court.

Judge Sutton addressed the issue in his opinion in Forman v. TriHealth33, stating as follows

But at the pleading stage, it is too early to make these judgment calls. ‘In the absence of further development of the facts, we have no basis for crediting one set of reasonable inferences over the other. Because either assessment is plausible, the Rules of Civil Procedure entitle [the three employees] to pursue [their imprudence] claim (at least with respect to this theory) to the next stage….34

This wait-and-see approach also makes sense given that discovery holds the promise of sharpening this process-based inquiry. Maybe TriHealth ‘investigated its alternatives and made a considered decision to offer retail shares rather than institutional shares’ because ‘the excess cost of the retail shares paid for the recordkeeping fees under [TriHealth’s] revenue-sharing model….’ Or maybe these considerations never entered the decision-making process. In the absence of discovery or some other explanation that would make an inference of imprudence implausible, we cannot dismiss the case on this ground. Nor is this an area in which the runaway costs of discovery necessarily cloud the picture. An attentive district court judge ought to be able to keep discovery within reasonable bounds given that the inquiry is narrow and ought to be readily answerable35

As Judge Sutton referenced, the court has a number of options available to control the costs of discovery. Judge Sutton was presumably talking about options such as “controlled” discovery, where a judge can limit discovery to only such facts and and documents relative to the case at hand. Presumably, the costs of such discovery could involve nothing more than copying costs, with perhaps some follow-up discovery and a few depositions. In some cases, follow-up requests for admisssions may provide the needed discovery information.

Judge Stein has been very consistent in refusing to dismiss plan participant claims at the pleading stage, preferring to allow participants’ claims to be decided on the merits rather than legal technicalities, especially when no discovery has been permitted. 36

One could argue that the Second Circuit has done the best job of summarizing and resolving the burden of proof regarding causation with the following observation in its Sacerdote opinion

If a plaintiff succeeds in showing that “no prudent fiduciary” would have taken the challenged action, they have conclusively established loss causation, and there is no burden left to “shift” to the fiduciary defendant.37

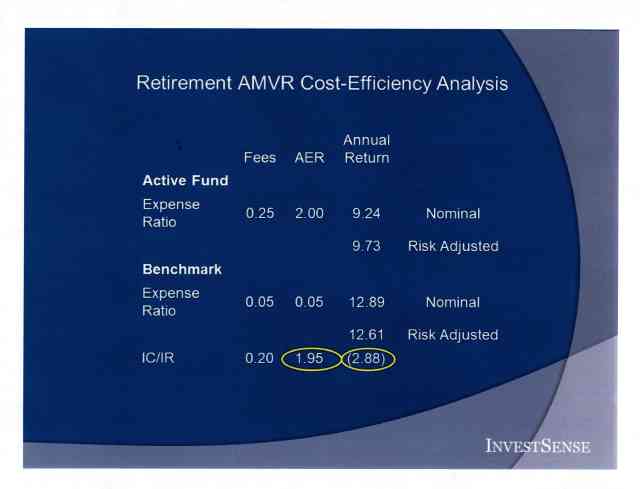

Makes perfect sense to me. The AMVR analysis below supports the Sacerdote’s argument. The fact that the actively managed fund significantly underperforms a comparable index fund, and is paying an incremental fee for the opportunity to do so is not consistent with prudent investing and establishes that the actively managed was not/is not a prudent choice for any retirement plan, especially when the compounding of both the loss due to both annual underperformance (-2.88) and the incremental fee (0.20). Plan sponsors should remember the studies of both the General Accountability Office and the DOL, studies that concluded that each additional one percent and costs reduces an investor’s end return by approximately 17 percent over a twenty year period. As John Bogle used to say, “Costs Matter.”

Costs matter even more when the correlation of returns between an actively managed mutual funds and a comparable passively managed/index fund, as shown in the middle column. The correlation of returns between the two funds shown was extremely high, 98. As a result, the effective incremental cost rose significantly, to 1.95 making the fiduciary imprudence of the active. combine with the 2.88 underperformance number the effective combined cost would be 4.83. Multiply that figure by 17 to calculate the projected cost using the DOL and GAO numbers. The Second Circuit’s Sacerdote quote is one all courts and investment fiduciaries should remember.

Retirement Security Rule Litigation

One could legitimately summarize the ongoing Retirement Security Rule (Rule) litigation38 in the Fifth Circuit with the acronym SNAFU. While both Judge Lynn in the district court and Judge Stewart in the Fifth Circuit39 recognized the need and appropriateness of the DOL’s proposal of the Rule, the Fifth Circuit’s decision to stay the Rule and, arguably, willful blindness in recognizing the fundamental issues with annuity products being recommended to retirees and the unwillingness to simply decide the case on its merits is frustrating, as it has delayed the ability to seek certiorari so that SCOTUS can decide this crucial issue and stop the abusive marketing strategies being perpetuated on retirees. The forensic breakeven analysis shown below is a perfect example of the motivating rationale behind the DOl’s proposal.

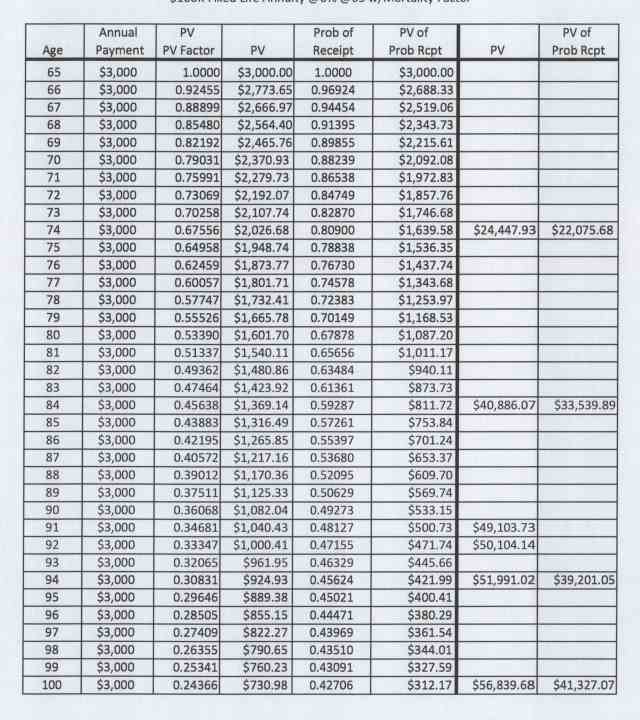

The following image represents a breakeven analysis for a 65 year-old woman annuitizing her $50,000 annuity at age 65, with the annuity paying 6 percent a year, and a life expectancy at age 65 of 21 years. Factoring in present value alone (to factor in the time value money), the breakeven point would fall somewhere between age 91 and 92. Given the annuity owner’s life expectancy of w21 years, the breakeven analysis would indicate that the annuity owner would not break even on her investment. Since most annuities have a reverter clause in their contract, this would indicate that the annuity issuer would eventually receive a windfall of the balance remaining in the annuity at the annuity owner’s death, assuming that the annuitant and the annuity owner are one and the same, as is often the case.

However, a properly prepared annuity breakeven analysis factors in both present value and mortality risk, the risk that the annuity owner will not live to collect the annual payments. Including mortality risk into the analysis indicates that the annuity owner would never break even. Even worse, the chart shows just how short the annuity owner would be from breaking even factoring in mortality, increasing the windfall that the annuity issuer would receive. This is a perfect example of why a well-known saying in the annuity industry is “annuities are sold, not bought.” Unfortunately, most plan sponsors, plan participants, and even annuity agents, do not know to properly prepare and analyze an annuity breakeven analysis. As a result, plan sponsors and plan participants fall victim the the “guaranteed income for life” ruse without address the “at what cost” part of the valuation equation.

In the case of the Rule, the DOL specifically mentioned the abuse and costs of fixed index annuities. As district court Judge Barbara Lynn noted in her opinion uphold the Rule, FIA issuers typically reserve the right to unilaterally change key terms of an FIA annually, including the interest rate to be paid. Why would any investor invest in a product clearly structured to put the annuity issuer’s best interests ahead of the annuity owner’s best interests. FIAs also have the same windfall issues as previously discussed. FIAs represent the worst aspects of annuities, and serve as a clear example of investors purchasing investments that are not in their best interests because they fall for the “guaranteed income for life” spiel without considering the costs of the product, both monetary costs as well as costs, such as loss of assets available for estate planning. This is why annuities are referred to as “estate planning saboteurs” among estate planning attorneys.

I believe that SCOTUS will uphold the Rule if the DOL can ever persuade the Fifth Circuit to make a ruling that the DOL can use to convince SCOTUS to grant certiorari and hear the case. The fear now is that the incoming administration being more pro-business and less concerned about investors, the new DOL will not pursue the case and being willing to allow investors to continue to be mislead and financially harmed by the annuity industry. A decision by SCOTUS upholding the Rule would presumably have a tremendous impact on the future of ERISA litigation, as the annuity industry pushes for greater involvement in ERISA retirement plans.

Notes

1. 29 CFR Part 2510 (Rule)

2. No. 24-3014 (6th Circuit 2024)

3. Cunnigham v. Cornell University, Supreme Court Case No. 23-1007 (2024)

4. “Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit Calls Out Brethren On Decision to Stay the Dol’s Retirement Security Rule” https://fiduciaryinvestsense.com/2024/09/25/chief-judge-of-the-5th-circuit-calls-out-his-brethren-on-decision-to-stay-the-dols-retirement-security-rule/ ; “Deja Vu All Over Again: Is the Annuity Industry Selling Annother Round of Annuity Misrepresentations Kool-Aid?” https://fiduciaryinvestsense.com/2024/09/02/deja-vu-all-over-again-is-the-annuity-industry-serving-a-second-round-of-annuity-misrepresentations-kool-aid/

5. Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. Hugler, 231 F. Supp. 3d 152, 190 (N.D. Tex. 2017) (Lynn decision)

6. Lynn decision.

7. Tibble v. Edison International, Inc, 135 S. Ct. 1823 (2015) (Tibble).

8. Tibble, 1828

9. 19 CFR , Part 2509 (IB 2015-01}

10. IB 2015-01.

11. IB 2015-01.

12. Restatement (Third) Trusts, Section 90, comment h(2).

13.Solicitor General Brotherston amicus brief https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/18/18-926/123904/20191127133744511_18-926%20Putnam.pdf (Brotherston amicus)

14. Brotherston amicus and Brotherston v. Putnam Investments, LLC, 907 F.3d 17 (2015)

15. Brotherston amicus , 8

16. Brotherston, 31

17. Brotherston, 31.

18. Brotherston, 37.

19. Brotherston, 37.

20. Brotherston, 36

21. Brotherston, 36.

22.. Brotherston amicus, 8

23. Brotherston amicus, 11.

24. Brotherston amicus, 11

25. Brotherston amicus, 11

26. Brotherston amicus, 17.

27. Solicitor General amicus brief, Cunningham v. Cornell University, 29, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/23/23-1007/333121/20241202200914652_23-1007tsacUnitedStates.pdf.(Cunningham amicus)

28. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 8.

29. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 9.

30. Cunningham amicus, 35.

31. Cunningham amicus, 35.

32. Cunningham amicus, 35.

33. Forman v. TriHealth, Inc., 40 F.4th 443 (TriHealth)

34. TriHealth, 450.

35. TriHealth, 450.

36. Leber v. Citigroup 401k Plan Investment Committee, 2014 WL 4851816.

37. Sacerdote v. New York University, 9 F.4th 95, and Cunningham amicus, 26

38. https://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/17/17-10238-cv0.pdf

39. Justice Carl E. Srewart dissent Retirement Security Rule litigation https://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/17/17-10238-cv0.pdf

40. Lynn decision.

Suggested Readings

© Copyright 2024 InvestSense, LLC. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.