James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP EmeritusTM, AWMA®

Most pension plans use mutual funds as the primary investment options within their plan. The Restatement of Trusts (Restatement) states that fiduciaries should carefully compare the costs and risks associated with a fund, especially when considering funds with similar objectives and performance.1 The Restatement advises plan fiduciaries that in deciding between funds that are similar except for their costs and risks, the fiduciary should only choose the fund with the higher costs if the fund “can reasonably be expected” to provide a commensurate return for such additional costs and/or fees.2

Given the historical underperformance of many actively managed mutual funds, factoring in commensurate returns can be a significant hurdle that pension plan fiduciaries too often fail to properly consider. A fund with higher costs that fails to provide a commensurate return to a plan participant, namely a higher positive incremental return than the fund’s incremetnal costs, has no inherent value to an investor and is clearly imprudent.

A common argument by the financial services industry, and even some courts, is that a fiduciary is not legally bound to select the least expensive investment option. However, that argument, focusing only on costs, can be misleading, as other factors must be considered. TIAA-CREF properly summed up a plan sponsor’s fiduciary obligations with regard to factoring in an investment’s costs, stating that

[p]lan sponsors are required to look beyond fees and determine whether the plan is receiving value for the fees paid. This should include an evaluation of vital plan outcomes, such as retirement readiness, based on their organization’s values and priorities.3

So, how does one determine whether a plan is “receiving value,” an actual benefit from a plan adviser’s advice? Businesses often use a cost/benefit analysis to determine whether to pursue a project based on the cost-efficiency of the project. When a cost/benefit analysis indicates that the projected costs exceed the projected benefits, the project is usually deemed cost-inefficient and is not worth pursuing.

A simple cost/benefit analysis would seem to be a part of a prudent process for plan sponsors to use evaluating the fiduciary prudence of investment products in defined contribution plans (DCPs). However, based on the evidence, very few plans seem to use cost/benefit analyses as part of their fiduciary prudence process. Furthermore, even when plans do use cost/benefit analysis, there are often legitimate questions as to whether such analyses were properly conducted.

An obvious question would be why some plans not use cost/benefit analyses in conducting their legally required independent and objective investigation and evaluation of investment options for their plan. Costs that exceed benefits would seem to be a simple enough standard.

Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that actively managed mutual funds continue to compose the majority of investment option within plans. Studies havev consistently shown that the overwhelming majority of actively managed mutual funds are cost-inefficient, as they fail to even cover their costs.

99% of actively managed funds do not beat their index fund alternatives over the long term net of fees.4

Increasing numbers of clients will realize that in toe-to-toe competition versus near–equal competitors, most active managers will not and cannot recover the costs and fees they charge.5

[T]here is strong evidence that the vast majority of active managers are unable to produce excess returns that cover their costs.6

[T]he investment costs of expense ratios, transaction costs and load fees all have a direct, negative impact on performance….[The study’s findings] suggest that mutual funds, on average, do not recoup their investment costs through higher returns.7

The Active Management Value RatioTM

Research has consistently shown that most people are more visually oriented when it comes to understanding and retaining information. Therefore, as a plaintiff’s attorney, I created a simply metric, the Active Management Value Ratio™ (AMVR) to provide a visual representation of the academic studies’ findings with regard to the performance of actively managed mutual funds, most notably the research of investment icons, including Nobel laureate Dr. William F. Sharpe, Charles D. Ellis, and Burton L. Malkiel.

[T]he best way to measure a manager’s performance is to compare his or her return with that of a comparable passive alternative.8

So, the incremental fees for an actively managed mutual fund relative to its incremental returns should always be compared to the fees for a comparable index fund relative to its returns. When you do this, you’ll quickly see that that the incremental fees for active management are really, really high—on average, over 100% of incremental returns.9

Past performance is not helpful in predicting future returns. The two variables that do the best job in predicting future performance [of mutual funds] are expense ratios and turnover.10

The beauty of the AMVR is its simplicity. In interpreting a fund’s AMVR scores, an attorney, fiduciary or investor only must answer two simple questions:

1. Does the actively managed mutual fund produce a positive incremental return?

2. If so, does the fund’s incremental return exceed its incremental costs?

If the answer to either of these questions is “no,” then the fund does not qualify as cost-efficient under the Restatement’s guidelines.

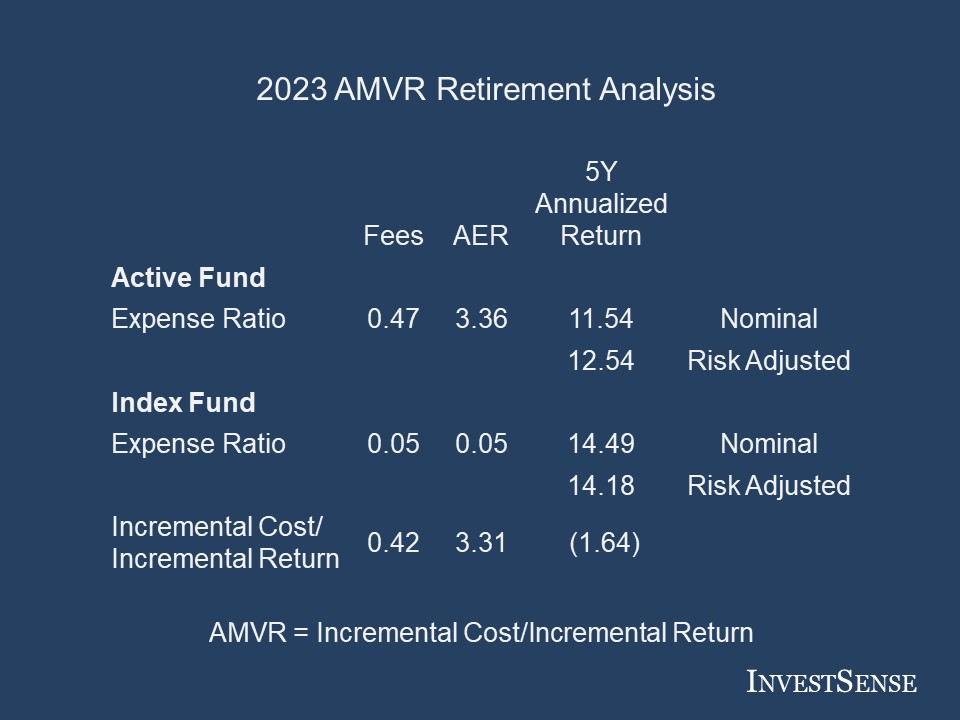

The AMVR slide shown above is a cost/benefit analysis comparing the retirement shares of two popular large cap growth mutual funds, one an actively managed fund, the other an index fund.

A simple analysis shows that the actively managed fund’s incremental costs exceed the fund’s incremental negative returns. Since costs exceed returns, this would result in the actively managed fund being cost-inefficient relative to the index fund for the time period studied.

The Securities and Exchange Commission and the General Accountability Office have both found that each additional 1 percent in costs/fees reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent over a twenty year period.11 If we treat the incremental underperformance of the actively managed fund as an opportunity cost, and combine that number with the incremental costs, based on the fund’s stated expense ratio, the projected loss in end-return would be approximately 35 percent.

But does the nominal/stated cost version of the AMVR actually reflect the costs incurred by plan participants if the actively managed fund is selected within a plan?

The Active Expense RatioTM

In a 2007 speech, then SEC General Counsel, Brian G. Cartwright, asked his audience to think of an investment in an actively managed mutual fund as a combination of two investments: a position in an “virtual” index fund designed to track the S&P 500 at a very low cost, and a position in a “virtual” hedge fund, taking long and short positions in various stocks. Added, together, the two virtual funds would yield the mutual fund’s combined costs.

The presence of the virtual hedge fund is, of course, why you chose active management. If there were zero holdings in the virtual hedge fund-no overweightings or underweightings-then you would have only an index fund. Indications from the academic literature suggest in many cases the virtual hedge fund is far smaller than the virtual index fund. Which means…investors in some of these … are paying the costs of active management but getting instead something that looks a lot like an overpriced index fund. So don’t we need to be asking how to provide investors who choose active management with the information they need, in a form they can use, to determine whether or not they’re getting the desired bang for their buck?12

Fortunately, Ross Miller introduced a metric, the Active Expense Ratio (AER), which allows fiduciaries and investors to perform the type of analysis Cartwright suggested. Miller explains the importance of the AER as follows:

Mutual funds appear to provide investment services for relatively low fees because they bundle passive and active funds management together in a way that understates the true cost of active management. In particular, funds engaging in ‘closet’ or ‘shadow’ indexing charge their investors for active management while providing them with little more than an indexed investment. Even the average mutual fund, which ostensibly provides only active management, will have over 90% of the variance in its returns explained by its benchmark index.13

In the AMVR example shown, using nothing more than just the actively managed fund’s r-squared number and its incremental cost, the AER estimates the actively managed fund’s implicit expense ratio to be 3.36, resulting in incremental correlation-adjusted expense ratio/costs of 3.31. Combined with the actively managed fund’s underperformance, and using the DOL’s and GAO’s findings, that would result in a projected loss of approximately 84 percent over a twenty year period.

The Fiduciary Prudence Ratio™

The AMVR provides all of the information needed to perform several types of cost/benefit analysis. The AMVR equation, incremental correlation-adjusted costs divided by incremental risk-adjusted return, provides an analysis of the premium paid by anyone investing in the actively managed mutual fund, relative to an investment in the benchmark index fund.

While the AMVR is simple enough, some have suggested that a more traditional metric focusing on return relative to costs would be more helpful and easier to uderstand. For some, the issue with the AMVR format seems to be that funds that do not produce a positive incremental return do not earn an AMVR rating.

The AMVR metric makes it easy to produce a more return-focused cost/benefit analysis by flipping the original equation so that the incremental risk-adjusted return becomes the numerator and the incremental risk-adjusted costs becomes the denominator. This new metric is known as the Fiduciary Prudence Ratio™ (FPR).

In using the FPR, the goal would be a ratio above 1.00, which would indicate that the actively managed fund’s incremental risk-adjusted return was greater than the fund’s incremental costs. The higher the fund’s FPR, the greater the value provided.

In the AMVR example shown above, the actively managed fund’s FPR would be zero due to the fund’s failure to provide a positive incremental risk-adjusted return. The zero score would indicate that the fund would be imprudent under the Restatement (Third) of Trust’s fiduciary prudence standards.

Some people have indicated an aversion to working with decimal points. In that case, simply multiply the FPR discussed above by 100 to get the more common 1-100 format. Anyone deciding to use the 1-100 format must keep in mind that the FPR score produced is a relative score, not an absolute score. In interpreting the FPR using the 1-100 format, a score above 100 would be needed to establish that the actively managed fund provided value, provided incremental risk-adjusted returns that were greater than the fund’s incremental costs.

While other benchmarks could obviously be tested, using either form of incremental costs as the numerator, the cost-consciousness/cost-efficiency requirements of the Restatement would also have to be considered.

Going Forward

[A plan sponsor’s fiduciary duties are] “the highest known to the law.”14

In reviewing some recent court decisions in DCP fiduciary breach actions, some courts have seemingly lost sight of ERISA’s stated goal, that being to protect workers and to help them prepare for retirement. Some courts rarely address the issue of whether the DCP’s investment options produce value for plan participants. As mentioned earlier, a prudent DCP investment option is one that is cost efficient, one whose benefits are at least commensurate with the fund’s extra cost and risks.

The problem for many DCP plan sponsors and other DCP fiduciaries is the history of consistent underperformance by many actively managed mutual funds relative to passively managed index funds. The FPR could reduce the time and costs of performing the legally required independent investigation and evaluation of each investment option chosen for a plan.

The simplicity of both the AMVR and the FPR should improve the quality of investments chosen for a DCP plan, thereby reducing the risk of litigation and unwanted fiduciary liability exposure. The combination of the AMVR and the FPR could easily expose situations where the plan adviser is not providing value for the plan or its participants, in which case a prudent plan sponsor should consider replacing the plan provider in order to reduce any potential future fiduciary liability exposure.

By combining the AMVR and the FPR, DCP plan sponsors should be able to use “humble arithmetic” to easily create and maintain win-win DCP plans that provides value for both the plan sponsor, the plan participants, and their beneficiaries.

Notes

1. Restatement (Third ) Trusts §90 cmt m. Copyright American Law Institute. All rights reserved.

2. Restatement (Third) Trusts §90 cmt h(2). Copyright American Law Institute. All rights reserved.

3. TIAA-CREF, “Assessing the Reasonableness of 403(b) Fees,” https://www.tiaa.org/public/pdf/performance/ReasonablenessoffeesWP_Final.pdf.

4. Laurent Barras, Olivier Scaillet and Russ Wermers, False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas, 65 J. FINANCE 179, 181 (2010).

5. Charles D. Ellis, The Death of Active Investing, Financial Times, January 20, 2017, available online at https://www.ft.com/content/6b2d5490-d9bb-11e6-944b-eb37a6aa8e.

6. Philip Meyer-Braun, Mutual Fund Performance Through a Five-Factor Lens, Dimensional Fund Advisors, L.P., August 2016.

7. Mark Carhart, On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance, 52 J. FINANCE, 52, 57-8 (1997).

8. William F. Sharpe, “The Arithmetic of Active Investing,” available online at https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/active/active.htm.

9. Charles D. Ellis, “Letter to the Grandkids: 12 Essential Investing Guidelines,” https://www.forbes.com/sites/investor/2014/03/13/letter-to-the-grandkids-12-essential-investing-guidelines/#cd420613736c

10. Burton G. Malkiel, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” 11th Ed., (W.W. Norton & Co., 2016), 460.

11. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study).

12. SEC Speech: The Future of Securities Regulation: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: October 24, 2007 (Brian G. Cartwright). http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2007/spch102407bgc.htm

13. Ross Miller, “Evaluating the True Cost of Active Management by Mutual Funds,” Journal of Investment Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, 29-49 (2007) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=746926.

14. Restatement of Trusts 2d § 2, comment b (1959). ” Donovan v. Bierwirth, 680 F.2d 263, 272 n.8 (2d Cir. 1982)

Copyright InvestSense, LLC 2024. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.