James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP EmeritusTM, AWMA®

As a fiduciary risk management counsel, I’m often asked about my opinion as to the biggest risk management mistake plan sponsors make. To me, the answer is simple. The biggest and most common fiduciary risk management mistake that I see investment fiduciaries make, including plan sponsors, is not knowing and understanding what the law does, and does not, require of them in their fiduciary capacity.

I recently gave a presentation on the “next big thing” in ERISA fiduciary litigation. Overall, I expect healthcare fiduciary litigation to continue to increase. I believe there is going to be an increase in fiduciary litigation involving in-plan annuities and annuities, in any form, in plans in general, including TDFs with an embedded annuity element.

The litigation liability area that I think is most promising for ERISA plaintiff attorneys is the inconsistency in standards between ERISA 404(a)1 and NAIC Rule 275.2 There is simply no middle ground.i I have heard some annuity advocates claim that NAIC Rule 275 provides a safe harbor for plan sponsors who choose to include annuities in their plans, despite the fact that there is no evidence to support such claims. Furthermore, Rule 275 explicitly exempts ERISA plans from Rule 275 coverage…3

Other annuity advocates point to the SECURE Acts as providing safe harbor protection for plan sponsors choosing to include annuities in their plans. The SECURE Acts provide a safe harbor in connection with the selection of an annuity provider, not the selection ofan annuity product. The prudence of an annuity itself is still subject to ERISA’s prudence and loyalty requirements.

I think the Achilles’ heel that ERISA plaintiff attorneys should focus on is the obvious inconsistency of the standards between ERISA 404(a) and NAIC rule 275 and the potential fiduciary liability that exists, liability which is going to completely blindslide many plan sponsors, as there has been little discussion on the issue. The issue is that annuity salespeople can be in compliance with Rule 275 while leaving plan sponsors unknowingly in violation of ERISA 404(a) due to the inconsistencies in the two standards.

§ 2550.404a-1 Investment duties.

In general. Sections 404(a)(1)(A) and 404(a)(1)(B) of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended (ERISA or the Act) provide, in part, that a fiduciary shall discharge that person’s duties with respect to the plan solely in the interests of the participants and beneficiaries; for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to participants and their beneficiaries and defraying reasonable expenses of administering the plan; and with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.

Compare that language to the NAIC’s suitability requirements in connection with the sale of annuities:

Section 1. Purpose A. The purpose of this regulation is to require producers, as defined in this regulation, to act in the best interest of the consumer when making a recommendation of an annuity and to require insurers to establish and maintain a system to supervise recommendations so that the insurance needs and financial objectives of consumers at the time of the transaction are effectively addressed

Section 4. Exemptions Unless otherwise specifically included, this regulation shall not apply to transactions involving: A. Direct response solicitations where there is no recommendation based on information collected from the consumer pursuant to this regulation; B. Contracts used to fund: (1) An employee pension or welfare benefit plan that is covered by the Employee Retirement and Income Security Act (ERISA); (2) A plan described by Sections 401(a), 401(k), 403(b), 408(k) or 408(p) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), as amended, if established or maintained by an employer;

Section 6. Duties of Insurers and Producers A. Best Interest Obligations. A producer, when making a recommendation of an annuity, shall act in the best interest of the consumer under the circumstances known at the time the recommendation is made, without placing the producer’s or the insurer’s financial interest ahead of the consumer’s interest. A producer has acted in the best interest of the consumer if they have satisfied the following obligations regarding care, disclosure, conflict of interest and

documentation:

Section 6 (1) (a) Care Obligation. The producer, in making a recommendation shall exercise reasonable diligence, care and skill to: (i) Know the consumer’s financial situation, insurance needs and financial objectives; (ii) Understand the available recommendation options after making a reasonable inquiry into options available to the producer; (iii) Have a reasonable basis to believe the recommended option effectively addresses the consumer’s financial situation, insurance needs and financial objectives over the life of the product, as evaluated in light of the consumer profile information;,

Not only does NAIC Rule 275 explicitly exempt ERISA plans from coverage under tthe Rule, it also does not require an annuity agent to factor in the best interests of the annuity owner’s beneficiaries when making recommendations involving annuities. It has been suggested to me that Rule 275 does not require consideration of the plan participant’s beneficiaries’ best interests because Rule 275 assumes that ERISA plans have access to experts who will ensure that the beneficiaries’ best interests have been considered. Experience has shown that such assumption is not supported by the evidence.

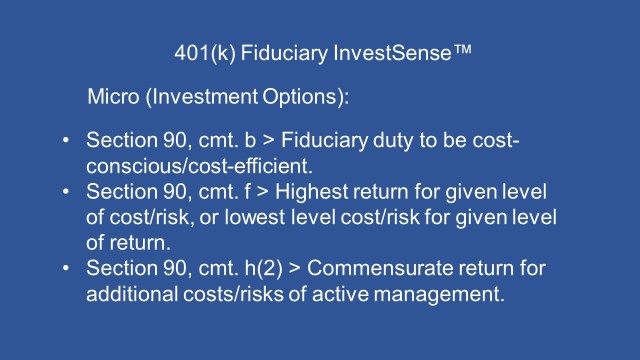

InvestSense, LLC, teaches our clients a simple two-step risk management process in analying potential investment options wihtina plan:

– Step One – Does ERISA or any other law/regulation expressly require that a plan offer the investment option be offered within a plan?

The answer is “no.” ERISA does not expressly require that any specific type of investment option be offered within a plan, only that all investment options offeredwithin a plan be legally prudent.

Step Two – Would/Could the investment option under consideration potentially expose the plan to unnecessary fiduciary liability?

If so, common sense should tell the plan to avoid the investment option. Plan participants interested in such products would still have the option of purchaing such investments outside of the plan, without potentially exposing the plan to unnecessary fiduciary risk.

With regard to annuities, we generally advise our clients to avoid them altogether, since plans have no legal obligation to provide such so-called “retirement income” products or strategies. Furthermore, most forensic techniques, such as breakeven analysis, prove that annuities are rarely in the best interests of either the plan participant or their benficiaries. As for annuity industry claims that plan participants “want’ such products, as a former securities compliance director, I always remember the annuity wholesalers stressing to our brokers that “annuities are sold, not bought.” As for self-serving annuity industry polls and surveys supporting such claims, plan sponsors have a legal obligation to comply with ERISA, not the alleged whims of some plan participants.

My experience has been that very few plan sponsors are aware of or have actually read ERISA 404(a) or NAIC Rule 275, choosing instead to blindly rely on the misrepresentations of annuity wholesalers and brokers, despite the warnings of the courts that such blind reliance on commissioned salespeople is not legally justified due to the obvious financial conflict of interest.

Defendants relied on FPA, however, and FPA served as a broker, not an impartial analyst. {Brokers} are not independent analysts. FPA does not work for the plan; rather, insurance companies like Transamerica pay [a broker’s salary.] As a broker, FPA and its employees have an incentive to close deals, not to investigate which of several policies might serve the union best. A business in FPA’s position must consider both what plan it can convince the union to accept and the size of the potential commission associated with each alternative. FPA is not an objective analyst any more than the same real estate broker can simultaneously protect the interests of both buyer and seller or the same attorney can represent both husband and wife in a divorce.4

See also: Bussian v. RJR Nabisco, Inc., 223 F.3d 286, 301(5th Cir. 2000) (fiduciaries may not “rely blindly” on advice); In re Unisys.,74 F.3d 420, 435-36 (3d. Cir. 1996).

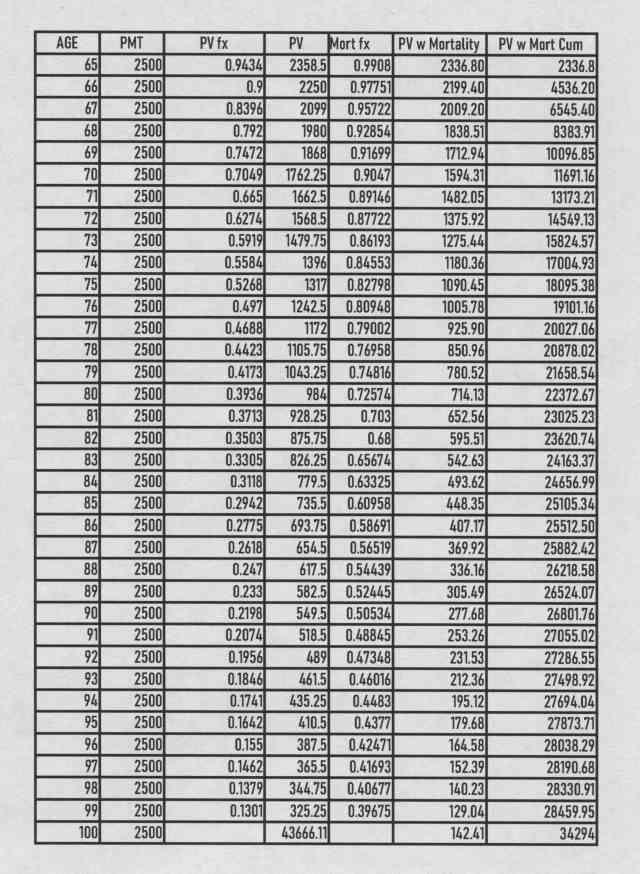

Fortunately, plan sponsors can independently evaluate the prudence of an annuity by performing an annuity breakeven analysis using Microsoft Excel. While a properly prepared breakeven should factor in both present value and mortality risk, a simple present value breakeven analysis using Excel often indicates the legal imprudence of an annuity based on present value considerations alone.

Going Forward

The key point to consider is that an adviser recommending an in-plan or another form of an annuity as an investment option in a plan may be in compliance with NAIC Rule 275, but may nevertheless place a plan sponsor in violation of ERISA 404(a) due to the inconsistency in standards. The fact that annuities often require the annuity owner to annuitize the annuity, i.e., surrender the annuity contract and the amount of their investment, in order to receive the alleged benefit of the annuity, the stream of retirement, with absolutely no guarantee of a commensurate rerturn means that the annuity issuer stands to receive a windall at the annuity owner’s expense. Courts dislike such inequitable situations, citing that equity law, a basic component of fiduciary law, abhors a windfall. Upon annuitization, the annuity issuer becomes the legal owner of the value within the annuity. So, there is typically nothing available for the annuity owner’s beneficiaries, a result that the plan sponsor “knew or should have known”, a foreseeable result that is an obvious violation of ERISA 404(a)’s requirement to act in the beneficiaries’ best interests and should have factored in deciding whether toan annuity within the plan..

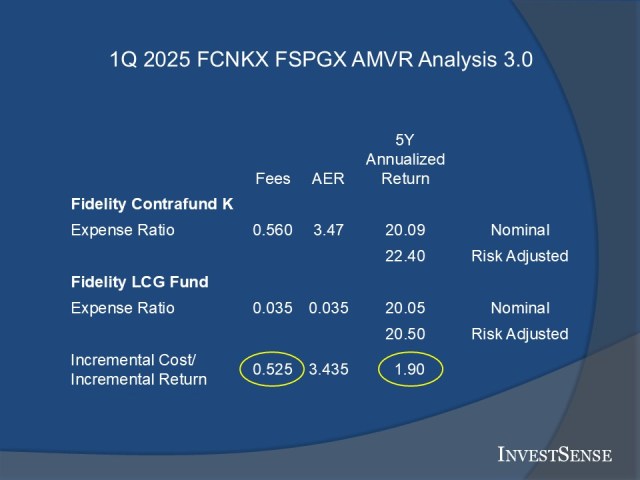

Annuity advocates will typically mention the availability of various “rider”s to address these issues. Unless they offer such riders for free (they don’t), there is the issue of the additional cost and the findings of both the General Accountability Office (GAO) and the Department of Labor (DOL) on the impact of cumulative fees and the compounding of same. Both the DOL and GAO determined that over a twenty-year period, each additional 1% in fees reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17%.

Therfore, plan sponsors considering annuities need to keep “3%” in mind, since 3 times 17 would result in plan participants and their beneficiaries losing 51 percent of their end-return. So, while annuity advocates may mention various riders, they often “forget” to mention the cumulative/compounding cost issue of the basic cost and fees of annuities. Adding the cost of riders would be expected to easily exceed the “3%” cumulative fees threshold, benefitting the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense, a clear breach of the fiduciary duty of loyalty..

One last piece of advice. Investment fiduciaries who receive a recommendation to include an annuity, any type of annuity, should always require the annuity salesperson to provide a written, properly prepared breakeven analysis on the annuity being recommended. A written analysis can be introduced into evidence, if necessary. Trial attorneys will tell you that you never want a case to become a “he said,” she said” situation. If the annuity salesperson refuses request to provide a written breakeven analysis showing the process they used (they will, they know the truth about their product. They just hope you don’t.) The the prudent plan sponsor will simply walk away.Fiduciary risk management often requires proactive strategies and measures by an investment fiduciary.

One last reminder for plan sponsors considering annuities, there is no such thing as “mulligans’ in fiduciary law! Heed the sound advice of former CEO Jack Welch – “Don’t make the process harder than it is.”

Notes

1. 29 U.S.C.A. Section 1104(a).

2. NAIC Rule 275 – Suitability in Annuity Transactions Model Regulation (Rule 275)

3. Rule 275, Section 4, “Exemptions,” B(2).

4. Gregg v. Transportation Workers of Am. Intern, 343 F.3d 833, 841 (6th Cir. 2003).

5. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study).

© Copyright 2025 InvestSense, LLC. All rights reserved

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

© Copyright 2025 InvestSense, LLC. All rights reserved

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.