Congress passed ERISA in 1974 as a “comprehensive statute designed to promote the interests of employees and their beneficiaries in employer benefit plans.”1

The past fifty years has seen significant changes in the market and in the number and types of investment products. These changes have resulted in the Department of Labor (DOL) proposing several changes to better protect employees and their beneficiaries in furtherance of ERISA’s stated goal and purposes.

Over the last forty years, the retirement-investment market has experienced a dramatic shift toward individually controlled retirement plans and accounts. Whereas retirement assets were previously held primarily in pension plans controlled by large employers and professional money managers, today, individual retirement accounts (“IRAs”) and participant-directed plans, such as 401(k)s, have supplemented pensions as the retirement vehicles of choice, resulting in individual investors having greater responsibility for their own retirement savings. This sea change within the retirement-investment market also created monetary incentives for investment advisers to offer conflicted advice, a potentiality the controlling regulatory framework was not enacted to address. In response to these changes, and pursuant to its statutory mandate to establish nationwide “standards . . . assuring the equitable character” and “financial soundness” of retirement-benefit plans, 29 U.S.C. § 1001, the Department of Labor (“DOL”) recalibrated and replaced its previous regulatory framework. To better regulate conflicted transactions as concerns IRAs and participant-directed retirement plans, the DOL promulgated a broader, more inclusive regulatory definition of investment-advice fiduciary under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”) and the Internal Revenue Code (“the Code”). Despite the relevant context of time and evolving marketplace events, Appellants and the panel majority skew valid agency action that demonstrates an expansive-but-permissible shift in DOL policy as falling outside the statutory bounds of regulatory authority set by Congress in ERISA and the Code. Notwithstanding their qualms with these regulatory changes and the effect the DOL’s exercise of its regulatory authority might have on certain sectors of the financial services industry, the DOL’s exercise was nonetheless lawful and consistent with the Congressional directive to “prescribe such regulations as [the DOL] finds necessary or appropriate to carry out [ERISA’s provisions].”2

In the decades following the passage of ERISA, the use of participant directed IRA plans has mushroomed as a vehicle for retirement savings. Additionally, as members of the baby-boom generation retire, their ERISA plan accounts will roll over into IRAs. Yet individual investors, according to DOL, lack the sophistication and understanding of the financial marketplace possessed by investment professionals who manage ERISA employersponsored plans. Further, individuals may be persuaded to engage in transactions not in their best interests because advisers like brokers and dealers and insurance professionals, who sell products to them, have “conflicts of interest.” DOL concluded that the regulation of those providing investment options and services to IRA holders is insufficient.3

The DOL recently introduced the Retirement Security Rule (Rule). In proposing the Rule, the DOL specifically questioned the inequitability and imprudence of recommendations of fixed indexed annuities (FIAs) and variable annuities (VAs) in connection with rollovers from qualified plans to individual retirements accounts (IRAs).

I recently addressed these same issues in a recent blog post discussing fiduciary law principles and annuities in general. Annuities are essentially bets, with the annuity issuer betting that the annuity owner will not receive a commensurate return on their original investment, typically resulting in a windfall for the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense. If the annuity investment was made in the context of a fiduciary relationship, such a potential reversion would seemingly constitute a breach of the fiduciary’s duty of loyalty, the duty to act solely in the best interests of the a plan participant and their beneficiaries.

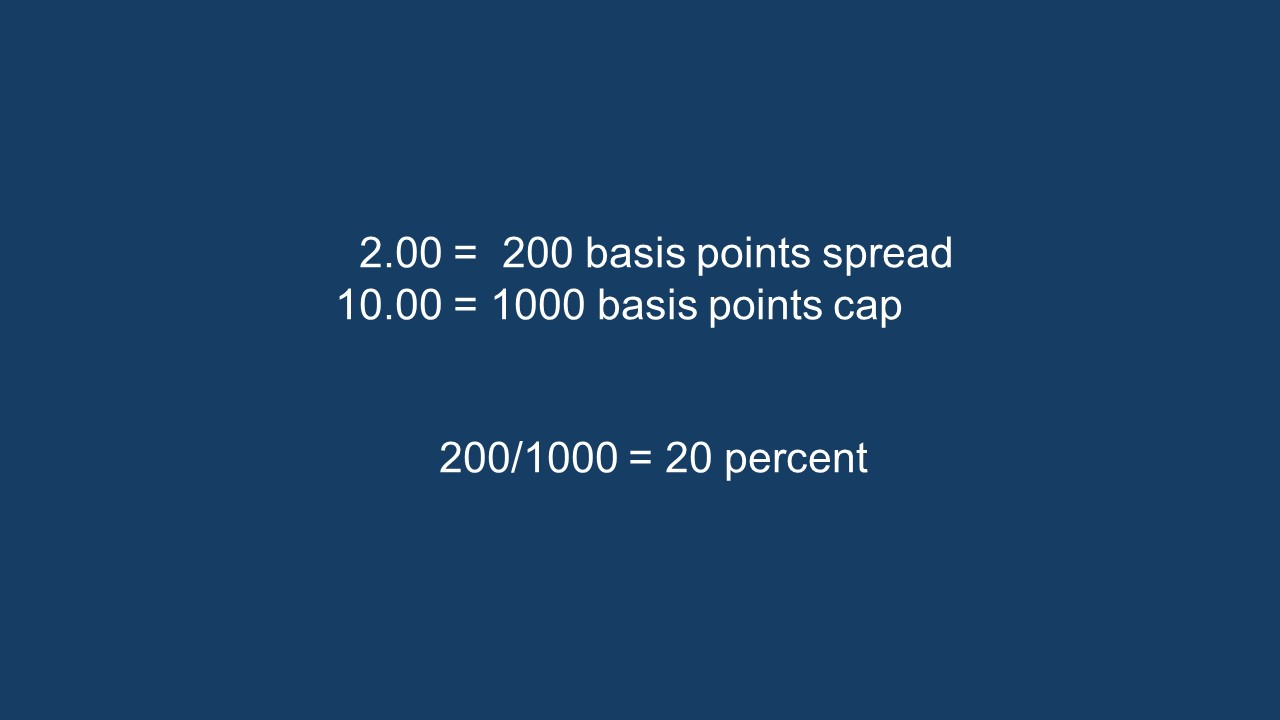

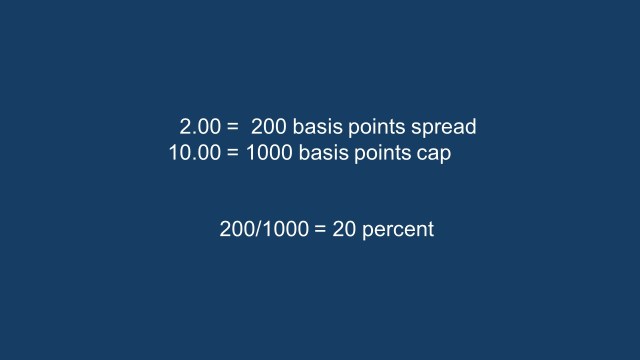

The “best interest” concern with regard to FIAs can be illustrated with one typical scenario, FIAs often combine a “spread” with a cap limiting the amount of return that an FIA can actually realize in one year. Although FIAs and the annuity industry in general rarely discount specifics such as the sperad they assess in connection with FIAs, combinations alleging a spread of 2 percent combined with a cap of 10 percent are common.

While the annuity industry would allege such a combination as a 2 percent spread and a cap of 10 percent. However, as the graphic shows, the actual impact on a FIA owner would be a 20 percent reduction in realized return. (Note: A basis point equals 1/100th of one percent (0.01). 100 basis points equals 1 1 percent.

This is the very type of abuse that led to the DOL’s Rule proposal, due to the complexity of FIAs and the confusing methodologies used in calculating the amount of interest credited to the FIA owner. This becomes even more problematic given the number of studies concluding that the majority of the public is functionally illiterate.

Against that backdrop and the confusion about the ongoing litigation inolving the DOL’s Rule, I constantly get asked for my opinion on the the 5th Circuit’s decision staying the Rule, including an explanation of the cases and how long it will be before these cases and their issues are resolved and plan participants aer fully protected under ERISA.

Naturally, no one can predict when the cases will be resolved and the stay lifted. However, I have found that providing plan sponsors and plan participants with an understandable summary of the decisions to date has been somewhat helpful to them, as they can evaluate the arguments being made and determine where the equities lie..

While everyone seemingly focused on the court’s decision to stay the Rule, then Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit dissented from the decision to stay the Rule, stating that

The panel’s majority conclusion that the DOL exceeded its regulatory authority by implementing the regulatory package that included a new definition of investment-advice fiduciary and both modified and created new exemptions to prohibited transactions is based on an erroneous interpretation of the grant of authority given by Congress under ERISA and the Code.4

Judge Stewart’s dissent incorporated both his own opinions, as well as those of district court Chief Judge Barbara G.M. Lynn. The fact that Judge Stewart referenced Judge Lynn’s earlier well-reasoned decision upholding the DOL’s Fiduciary Rule is interesting and may prove insightful as the litigation on the Rule winds its way throught the legal system. as Judge Lynn’s opinion addresses and rationalizes some of the key issues involved in the current litigation involving the Rule.

Judge Stewart initially noted the changes in both the market and investment products available since ERISA’s enactment

Over the last forty years, the retirement-investment market has experienced a dramatic shift toward individually controlled retirement plans and accounts. Whereas retirement assets were previously held primarily in pension plans controlled by large employers and professional money managers, today, individual retirement accounts (“IRAs”) and participant-directed plans, such as 401(k)s, have supplemented pensions as the retirement vehicles of choice, resulting in individual investors having greater responsibility for their own retirement savings. This sea change within the retirement-investment market also created monetary incentives for investment advisers to offer

conflicted advice, a potentiality the controlling regulatory framework was not

enacted to address.5

Judge Stewart then explained that the DOL proposed the Rule to address supposed gaps resulting from such changes over time in order to better protect plan participants, in furtherance of ERIAS’s stated goals.

Despite the relevant context of time and evolving marketplace events, Appellants and the panel majority skew valid agency action that demonstrates an expansive-but-permissible shift in DOL policy as falling outside the statutory bounds of regulatory authority set by Congress in ERISA and the Code. Notwithstanding their qualms with these regulatory changes and the effect the DOL’s exercise of its regulatory authority might have on certain sectors of the financial services industry, the DOL’s exercise was nonetheless lawful and consistent with the Congressional directive to ‘prescribe suchregulations as [the DOL] finds necessary or appropriate to carry out [ERISA’sprovisions].6

One of the main points of contention argued by the majority in deciding to stay the enforcement of the Rule was the proposed changes in the original five-part fiduciary test adopted by the DOL. However, as Judge Stewart points out

For 41 years, the DOL employed a five-part test to determine whether a person is an investment-advice fiduciary under ERISA and the Code, and that test limited the reach of the statutes’ prohibited transaction rules to those who rendered advice “on a regular basis,” and to instances where such advice “serve[d] as a primary basis for investment decisions with respect to plan assets.” See 29 C.F.R. § 2510.3–21(c)(1) (2015). This regulation “was adopted prior to the existence of participant-directed 401(k) plans, the widespread use of IRAs, and the now commonplace rollover of plan assets” from Title I plans to IRAs, thus leaving out of ERISA’s regulatory reach many investment professionals, consultants, and advisers who play a critical role in guiding plans and IRA investments. Fiduciary Rule, 81 Fed. Reg. 20,946.7

ERISA expressly authorizes the DOL to adopt regulations defining ‘technical and trade terms used’ in the statute. 29 U.S.C. 1135 8 @51

In 1975, DOL promulgated a five-part conjunctive test for determining

who is a fiduciary under the investment-advice subsection. Under that test,

an investment-advice fiduciary is a person who (1) “renders advice…or makes

recommendation[s] as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling

securities or other property;” (2) “on a regular basis;” (3) “pursuant to a mutual

agreement…between such person and the plan;” and the advice (4) “serve[s] as

a primary basis for investment decisions with respect to plan assets;” and (5) is

“individualized . . . based on the particular needs of the plan.”9 29 C.F.R.

§ 2510.3-21(c)(1) (2015).The rule challenged on appeal addresses these and other changes in the retirement investment advice market by, inter alia, abandoning the five-part test in favor of a definition of fiduciary that includes “recommendation[s] as to the advisability of acquiring . . . investment property that is rendered pursuant to [an] . . . understanding that the advice is based on the particular investment needs of the advice recipient.10

The DOL’s interpretation of “renders investment advice” is reasonably

and thoroughly explained. The new interpretation fits comfortably with thepurpose of ERISA, which was enacted with “broadly protective purposes” and which “commodiously imposed fiduciary standards on persons whose actionsaffect the amount of benefits retirement plan participants will receive”. In light of changes in the retirementinvestment advice market since 1975, mentioned above, the DOL reasonably concluded that limiting fiduciary status to those who render investment advice to a plan or IRA “on a regular basis” risked leaving retirement investors inadequately protected. This is especially so given that “one-time transactions like rollovers will involve trillions of dollars over the next five years and can be among the most significant financial decisions investors will ever make.”11@59Consistent with this broad authority, the DOL granted exemptions for otherwise prohibited transactions in the newregulatory package, but conditioned those exemptions on, among other things,a requirement that the fiduciary take on the same duties of “prudence” and “loyalty” that bind Title I fiduciaries.12 @60

Further, before making the relevant amendments to theexemptions, the DOL comprehensively assessed existing securities regulation for variable annuities, state insurance regulation of all annuities, and consulted with numerous government and industry officials, including the SEC, the Department of the Treasury, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, among others. The DOL found the protections prior to the current rulemaking insufficient to protect investors and acted within its prerogative tomodify the regulatory regime as it deemed necessary.13

In response to the annuity industry’s false claims that the Rule prohibits advisers, agents and broker-dealers from receiving commissions, Judge Stewart refutes such claims by pointing out that

As an initial matter, the DOL’s final rules do not prohibit commissions for broker-dealers. The rules only modify already-existing exemptions from prohibited transactions. As hasbeen the case, if a person or entity qualifies for an exemption, the applicant

can still receive commissions and other forms of third party compensation.14 @55

The real reason the insurance/annuity industry adamantly opposes the Rule and any other regulation that iattempts to impose a duty of loyalty or prudence on them is that they fully realize that, as currently structures, their annuities are not in the “best interest” of customers. As a result, they cannot currently pass any true fiduciary standard. I addressed these industry wide “best interest”/fiduciary imprudence issues in a recent post.

The immediate action involves the question of whether the Fifth Circuit met the conditions set out in the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) required for staying the DOL’s Rule, namely that the movant shows (1) a substantial likelihood of success on the merits; (2) a substantial threat of irreparable harm; (3) that the balance of hardships weighs in the movants’s favor; and (4) that issuance of a preliminary injunction will not disservice the public interest.

As to the last requirement regarding disservice of the public interest, a leading ERISA attorney has already suggested that that is exactly what will happen due the Fifth Circuit’s staying the efffectiveness of the Rule., with her observation that “[a]rguably the most impacted parties then are the investors these individuals serve that aren’t provided service as an ERISA fiduciary.”15

In summarizing the current issues involving the majority decision to stay the effectiveness of the Rule, Judge Stewart stated that

Here, in contrast, the DOL has acted within its delegated authority to regulate

financial service providers in the retirement investment industry—which it

has done since ERISA was enacted—and has utilized its broad exemption

authority to create conditional exemptions on new investment-advice

fiduciaries. That the DOL has extended its regulatory reach to cover more

investment-advice fiduciaries and to impose additional conditions on conflicted transactions neither requires nor lends to the panel majority’s conclusion that it has acted contrary to Congress’s directive.16

As mentioned earlier, Judge Stewart cites district court Chief Judge Lynn’s previous detailed and well-reasoned opinion upholding the Rule. . As to coverage under the Rule and commissions, Judge Lynn stated that :

Plaintiffs argue the Fiduciary Rule exceeds the coverage of ERISA because it imposes fiduciary status on those who earn a commission merely for selling a product, regardless of whether advice is given. Actually, the Fiduciary Rule plainly does not make one a fiduciary for selling a product without a recommendation. The rule states:

[I]n the absence of a recommendation, nothing in the final rule would make a person an investment advice fiduciary merely by reason of selling a security or investment property to an interested buyer. For example, if a retirement investor asked a broker to purchase a mutual fund share or other security, the broker would not become a fiduciary investment adviser merely because the broker purchased the mutual fund share for the investor or executed the securities transaction. Such ‘purchase and sales’ transactions do not include any investment advice component. Because Plaintiffs’ contention is directly contradicted by the plain language of the Fiduciary Rule, the Court rejects it. 17

As to the Rule replacing the original industry five-step fiduciary test’s “regular basis” requirement argument

Plaintiffs argue the first and third prongs of ERISA’s definition of fiduciary require a “meaningful, substantial, and ongoing relationship to the plan,” and that advice must be “provided on a regular basis and through an established relationship,” as had been required by the five-part test. Nothing in ERISA suggests “investment advice” was intended only to apply to advice provided on a regular basis, and the plain language of the first and third prongs do not indicate that an ongoing relationship is required. To the contrary, all three prongs are broad and written disjunctively; a person is a fiduciary if he satisfies any of the three prongs.18

Plaintiffs also claim that the first and third prongs of ERISA’s definition of a fiduciary involve a direct connection to the essentials of plan operation and that management and administration of a plan are central functions; as a result, they argue the second prong must be read consistently with the other two subsections, and a meaningful and substantial role of the fiduciary, that is ongoing, is required. It is true that the first prong addresses management and the third prong addresses administration, but that does not lead to the conclusion advocated by Plaintiffs. The second prong does not require a “meaningful, substantial, and ongoing relationship” with the recipient of the investment advice, nor must such advice be given on a regular basis for the adviser to qualify as a fiduciary. That is not required by the statute, and Plaintiffs’ attempt to read that into the language of the second prong is unpersuasive.19

Plaintiffs argue that because Congress has repeatedly amended ERISA since 1975, without ever amending the five-part test, that test has de facto been incorporated into ERISA by way of ratification. Generally, congressional inaction “deserves little weight in the interpretive process … [and] lacks persuasive significance because several equally tenable inferences may be drawn from such inaction. At the same time, if Congress “frequently amended or reenacted the relevant provisions without change … [Congress] at least understood the interpretation as statutorily permissible.20

The DOL has defined what it means to render investment advice since 1975, and decided its new interpretation is more suitable given the text and purpose of ERISA, along with new marketplace realities. Congress has neither ratified the five-part test nor has it excluded other interpretations not precluded by the statute.21

Plaintiffs argue the DOL’s interpretation of what it means to render investment advice is entitled to no deference, because ERISA requires regular contact between an investor and a financial professional to trigger a fiduciary duty. If anything, however, the five-part test is the more difficult interpretation to reconcile with who is a fiduciary under ERISA. The broad and disjunctive language of ERISA’s three prong fiduciary definition suggests that significant one-time transactions, such as rollovers, would be subject to a fiduciary duty. Under the five-part test, however, such a transaction would not trigger a fiduciary duty. This outcome is seemingly at odds with the statute’s text and its broad remedial purpose, especially given today’s market realities and the proliferation of participant-directed 401(k) plans, investments in IRAs, and rollovers of plan assets to IRAs. An interpretation covering such transactions better comports with the text, history, and purposes of ERISA.22

ERISA was enacted to serve broad protective and remedial purposes; as the Supreme Court explained, “Congress commodiously imposed fiduciary standards on persons whose actions affect the amount of benefits retirement plan participants will receive.”23

On the issue of whether the Rule is consistent with Congress’ intent in enacting ERISA

“remedial statutes are to be construed liberally,24

the DOL may “prescribe such regulations as [it] finds necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of [ERISA],” and to “define [the] accounting, technical and trade terms used in [ERISA].”Plaintiffs argue the Fiduciary Rule contradicts congressional intent because it in effect rejects the “disclosure regime established by Congress under the securities laws.” However, ERISA was enacted on the premise that the then-existing disclosure requirements did not adequately protect retirement investors, and that more stringent standards of conduct were necessary.25

Although ERISA includes disclosure requirements, it also imposes “standards of conduct, responsibility, and obligation[s]” for fiduciaries. The DOL’s new rules comport with Congress’ expressed intent in enacting ERISA. As a result of as the rulemaking process, the DOL rejected a disclosure-only regime, finding that disclosure was ineffective to mitigate the problems ERISA sought to remedy.26

The DOL may change existing policy “as long as [it] provide[s] a reasoned explanation for the change … and show[s] there are good reasons for the new policy.27

Here, the DOL concluded that the five-part test significantly narrowed the breadth of the statutory definition of a fiduciary under ERISA, allowing advisers “to play a central role in shaping plan and IRA investments, without ensuring the accountability that Congress intended for persons having such influence and responsibility.” In reversing that approach, the DOL found the Fiduciary Rule more closely reflected the scope of ERISA’s text and purposes. This reasoning, and the rest of what the DOL produced in the administrative record, satisfy the requirement that the agency explain the change.28

As to the fiduciary “best interest” issues with FIAs and VAs, Judge Lynn observed that:

The DOL explained how FIA sales can generate conflicts of interest, and that with increased sales of FIAs there have been additional complaints that the products were sold to customers who did not need them. The DOL noted a perceived relationship between increased sales of FIAs and unusually high commissions, which are typically higher than for fixed rate annuities. The DOL also noted that FINRA and the SEC concluded that FIAs are riskier than fixed rate annuities, citing FINRA’s conclusion that FIAs “are anything but easy to understand” and “give you more risk (but more potential return) than [a fixed rate annuity].29

The DOL found FIAs “are as complex as variable annuities, if not more complex,” that “[s]imilar to variable annuities, the returns of [FIAs] can vary widely, which results in a risk to investors,” and that “[u]nbiased and sound advice is important to all investors but it is even more crucial in guarding the best interests of investors in [FIAs] and variable annuities.” FIA sales are also “rapidly gaining market share compared to variable annuity sales.” The DOL determined that “[b]oth categories of annuities, variable and [FIAs], are susceptible to abuse, and Retirement Investors would equally benefit in both cases from the protections of [BICE].” The DOL also determined that placing FIAs and variable annuities in BICE would “create a level playing field” and “avoid[ ] creating a regulatory incentive to preferentially recommend indexed annuities.”30

The standard for determining whether the DOL’s decision to move FIAs from PTE 84–24 to BICE was arbitrary and capricious is “whether the agency examined the pertinent evidence, considered the relevant factors, and articulated a reasonable explanation for how it reached its decision.” The administrative record shows the DOL met this standard.31

The DOL described the complexity of FIAs in its Regulatory Impact Analysis (“RIA”). The RIA explained that FIAs generally provide “crediting for interest based on changes in a market index,” but noted there are hundreds of indexed annuity products, thousands of index annuity strategies, and that “the selection of the crediting index or indices is an important and often complex decision.” Further, there are several methods for determining changes in the index, with different methods resulting in varying rates of return. Rates of return are also affected by “participation rates, cap rates, and the rules regarding interest compounding.” Because “insurers generally reserve rights to change participation rates, interest caps, and fees,” FIAs can “effectively transfer investment risks from insurers to investors.” The DOL found that FIAs may offer guaranteed living benefits, but such benefits “may come at an extra cost and, because of their variability and complexity, may not be fully understood by the consumer.” The DOL also cited the SEC, which recently stated, “[y]ou can lose money buying an indexed annuity … even with a specified minimum value from the insurance company, it can take several years for an investment in an indexed annuity to break even.”32

The DOL comprehensively assessed existing securities regulation for variable annuities, state insurance regulation of all annuities, academic research, government and industry statistics on the IRA marketplace, and consulted with numerous government and industry officials, including the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (“NAIC”), SEC, FINRA, the Department of the Treasury, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Council of Economic Advisers, and the National Economic Council. The DOL found the protections prior to the current rulemaking insufficient to protect investors.33

The DOL found the annuity market to be influenced by contingent commissions, which “align the insurance agent or broker’s incentive with the insurance company, not the consumer,” that existing protections do not “limit or mitigate potentially harmful adviser conflicts,” and that “notwithstanding existing [regulatory] protections, there is convincing evidence that advice conflicts are inflicting losses on IRA investors.” The DOL found the conflicts would cost investors “at least tens and probably hundreds of billions of dollars over the next 10 years … despite existing consumer protections,” and that “the material market changes in the marketplace since 1975 have rendered [prior regulation] obsolete and ineffective.”34

In particular, today’s marketplace [commissions] … give[ ] … advisers a strong reason, conscious or unconscious, to favor investments that provide them greater compensation rather than those that may be most appropriate for the participants … an ERISA plan investor who rolls her retirement savings into an IRA could lose 6 to 12 and possibly as much as 23 percent of the value of her savings over 30 years of retirement by accepting advice from a conflicted financial adviser.”35

The DOL also found that state insurance laws and their enforcement vary significantly because only thirty-five states have adopted the NAIC model regulation, producing inconsistent protections and confusion for consumers. The U.S. Department of the Treasury noted that the absence of a national standard is problematic because there are unprecedented numbers of retirement investors, and financial professionals are selling increasingly complex products, therefore more uniform regulation is necessary to protect investors.36

The DOL determined the new rules would work with and complement state insurance regulations.37

Judge Lynn summarized the current environment and the need and appropriateness of the Rule by stating that

The extensive changes in the retirement plan landscape and the associated investment market in recent decades undermine the continued adequacy of the original approach in PTE 84–24. In the years since the exemption was originally granted in 1977, the growth of 401(k) plans and IRAs has increasingly placed responsibility for critical investment decisions on individual investors rather than professional plan asset managers. Moreover, at the same time as individual investors have increasingly become responsible for managing their own investments, the complexity of investment products and range of conflicted compensation structures have likewise increased. As a result, it is appropriate to revisit and revise the exemption to better reflect the realities of the current marketplace.38

So, going back and evaluating whether the Court sastisfied the APA’s requirement with regard to their decision to stay the Rule, one could justifiably argue that the Fifth Circuit seemingly just announced that the industry would prevail, arguably on a bootstrapped argument based largely on the court’s unquestioned acceptance of the annuity industry’s unproven allegations, with no indication that the court even considered the DOL’s statement that FIAs cause an annual loss of $17 billion anually.

Furthermore, unlike with Judge Lynn’s opinion, the Fifth Circuit’s opinion provides there no evidence that the Fifth Circuit factored in the inherent structural problems of FIAs and VAs, including the fact the fact that FIAs typically retain the right to unilaterally change the various terms that affect a FIA owner’s realized return. In short, no discussion of the the process that the Fifth Circuit used to balance the interest and determine that movant’s interest were more important. the conspicuous lack of any such numerical injuries in connection with particpants wonders how meaningful and balanced the consideration of such matters was, especially given the ease with which the annuity industry can impose conditions and restrictions that result in reducing a FIA investor’s realized return by 20 percent or more per year.

And yet, the Fifth Circuit’s decision to stay the Rule and prevent implementation of the Rule condones such financially harmful inequitable practices. In analyzing the Fifth Circuit’s decision to stay the effectiveness of the Rule, I have offered the analogy of a hit-and-run driver. The Fifth Circuit’s arguments willfully ignore the potential and permanent harm inflicted by just one imprudent “hit-and-run” annuity transaction.

The Court seemingly based it’s conclusion that the annuity advocates would prevail on the merits based on (1) numerous large alleged damages that the annuity industry would sustain as a result of the rule, and (2) the Court’s allegation that the Rule was otherwise inconsistent with ERISA. As for the alleged damages, the annuity advocates suggested that the alleged costs could threaten the existence of the annuity industry. 39 (5th @10). Specific projected losses included more than half a billion dollars in compliance costs, another $2.5 billion in costs over the next decade. The Court quickly responded that even the DOL’s projected costs was sufficient to establish irreparable injury.

Interestingly, the Court never mentioned the fact that the DOL referenced annual losses of $17 billion annually due to fixed indexed annuities (FIAs), or the fact that the annuity advocates numbers were purely speculative since they involved future projections.

I would caution the Court against unquestioningly accepting the annuity advocate’s damages estimates. I would remind the Court of the annuity industry’s intentional misleading of the courts in connection with the industry’s efforts to convince courts to require annuities and structured settlements in cases involving significant damages, with the industry promoting a “squandering plaintiff” ruse. In support of their campaign, they claimed to have studies showing that 95 percent of plaintiffs receiving lump sum settlements dissipated the settlement proceeds within five years.

Jeremy Babener, a well-known and respected settlement expert, exposed the “squandering plaintiff” ruse in a legal article, finding that

Although widely cited to justify the tax favored treatment of structured settlements, the statistical data relied upon [in arguing the “squandering plaintiff] is an oft-repeated urban myth of unsubstantiated origin. The statistical data does not, in fact exist….[From] a policy standpoint, the fundamental im0portance of the subsidy demands more than anecdotal evidence. A policy that impacts millions of [people] is deserving of a substantial empirical foundation.40

Babener also noted that when one industry general counsel was questioned about evidence behind the “squandering plaintiff” argument, the attorney admitted that he believed that much of the dissipating claimant argument was “imagined.”41

Fortunately, the courts eventually saw through the “squandering plaintiff” ruse. As a result, the courts now generally require the annuity industry to supply documentation to the court indicating what the actual costs the insurer will incur in purchasing a proposed annuity. The injured plaintiff generally also has the option to request the court to establish a so-called “qualified settlement fund (QSF), which allows the plaintiff to receive settlement funds and look for a fair annuity. without being subject to immediate taxation on such settlement funds.

As a plaintiff’s attorney, the damage caused by the annuity industry in promoting the “squandering plaintiff” ruse is indelibly lodged in my mind, as it effectively resulted in the annuity industry “victimizing the victims,” the annuity industry’s unethical acts and conscious disregard for people who had suffered life changing injuries and could least afford the harm resulting from the ruse perpetrated by the annuity industry. Hopefully, as this case progresses throught the legal system, future courts will consider the “hit-and-run” analogy and protect plan participants in reviewing the applicable evidence and by upholding the Rule in connection with every single transaction covered under the Rule.

Two quotes that seem relevant in connection with the Retirement Security Rule litigation are:

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence. – President John Adams

The truth is, we always know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it. – General Norman Schwartzko

Going back to the 2 percent spread on a FIA capped at an annual return of 10 return, resulting in a 20 percent in the FIA owner’s realized return, this is exactly the type of inequitable “hit-and-run” conduct that the Fifth Circuit’s decision to stay the Rule effectively condones. One can only assume that the Fifth Circuit did not understand the math involved, as its hard to beleive that any court would knowingly approve of such inequitable results and the resulting financial harm created on retirees.

Both Chief Judge Stewart and Chief Judge seemingly felt the same way in arguing that the DOL Rule was a permissible and necessary exercise of power by the DOL. Once again, as Chief Judge Stewart acknowledged the impact of change over time and the need for regulations to change proactively and appropriately in order to protect plan participants:

Despite the relevant context of time and evolving marketplace events, Appellants and the panel majority skew valid agency action that demonstrates an expansive-but-permissible shift in DOL policy as falling outside the statutory bounds of regulatory authority set by Congress in ERISA and the Code. Notwithstanding their qualms with these regulatory changes and the effect the DOL’s exercise of its regulatory authority might have on certain sectors of the financial services industry, the DOL’s exercise was nonetheless lawful and consistent with the Congressional directive to “prescribe such regulations as [the DOL] finds necessary or appropriate to carry out [ERISA’s provisions].” 42

Chief Judge Lynn’s expressed similar sentiments

the DOL may “prescribe such regulations as [it] finds necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of [ERISA],” and to “define [the] accounting, technical and trade terms used in [ERISA].”43

ERISA was enacted on the premise that the then-existing disclosure requirements did not adequately protect retirement investors, and that more stringent standards of conduct were necessary. Although ERISA includes disclosure requirements, it also imposes “standards of conduct, responsibility, and obligation[s]” for fiduciaries. The DOL’s new rules comport with Congress’ expressed intent in enacting ERISA. As a result of as the rulemaking process, the DOL rejected a disclosure-only regime, finding that disclosure was ineffective to mitigate the problems ERISA sought to remedy.44

Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. Hugler, 231 F. Supp. 3d 152, 175 (N.D. Tex. 2017)

The DOL enacted the Rule because it justifiably found that there was no meaningful oversight of FIAs, resulting in an annual loss of approximately $17 billion a year, with no sign that the state insurance commissioners and/or the NAIC were going to do anything to address the problem to protect plan participants. History definitely supports the DOL’s conclusions, given the laissez faire approach to compliance and enforcement of most state insurance commissioners.

Judge Lynn provided a detailed and excellent analysis of this issue

The DOL described the complexity of FIAs in its Regulatory Impact Analysis (“RIA”). The RIA explained that FIAs generally provide “crediting for interest based on changes in a market index,” but noted there are hundreds of indexed annuity products, thousands of index annuity strategies, and that “the selection of the crediting index or indices is an important and often complex decision.” Further, there are several methods for determining changes in the index, with different methods resulting in varying rates of return. Rates of return are also affected by “participation rates, cap rates, and the rules regarding interest compounding.” Because “insurers generally reserve rights to change participation rates, interest caps, and fees,” FIAs can “effectively transfer investment risks from insurers to investors.” The DOL found that FIAs may offer guaranteed living benefits, but such benefits “may come at an extra cost and, because of their variability and complexity, may not be fully understood by the consumer.” The DOL also cited the SEC, which recently stated, “[y]ou can lose money buying an indexed annuity … even with a specified minimum value from the insurance company, it can take several years for an investment in an indexed annuity to break even.45

The evidence clearly shows that the Fifth Circuit’s allegations that the the DOL acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” simply have no merit. The DOL explained how FIA sales can generate conflicts of interest, and that with increased sales of FIAs there have been additional complaints that the products were sold to customers who did not need them. The DOL noted a perceived relationship between increased sales of FIAs and unusually high commissions, which are typically higher than for fixed rate annuities. The DOL also noted that FINRA and the SEC concluded that FIAs are riskier than fixed rate annuities, citing FINRA’s conclusion that FIAs “are anything but easy to understand” and “give you more risk (but more potential return) than [a fixed rate annuity].”46

The DOL found the annuity market to be influenced by contingent commissions, which “align the insurance agent or broker’s incentive with the insurance company, not the consumer,” that existing protections do not “limit or mitigate potentially harmful adviser conflicts,” and that “notwithstanding existing [regulatory] protections, there is convincing evidence that advice conflicts are inflicting losses on IRA investors.” The DOL found the conflicts would cost investors “at least tens and probably hundreds of billions of dollars over the next 10 years … despite existing consumer protections,” and that “the material market changes in the marketplace since 1975 have rendered [prior regulation] obsolete and ineffective.”47

[T]oday’s marketplace [commissions] … give[ ] … advisers a strong reason, conscious or unconscious, to favor investments that provide them greater compensation rather than those that may be most appropriate for the participants … an ERISA plan investor who rolls her retirement savings into an IRA could lose 6 to 12 and possibly as much as 23 percent of the value of her savings over 30 years of retirement by accepting advice from a conflicted financial adviser.”48

The DOL also found that state insurance laws and their enforcement vary significantly because only thirty-five states have adopted the NAIC model regulation, producing inconsistent protections and confusion for consumers. The U.S. Department of the Treasury noted that the absence of a national standard is problematic because there are unprecedented numbers of retirement investors, and financial professionals are selling increasingly complex products, therefore more uniform regulation is necessary to protect investors.49

Judge Lynn then noted that with all these considerations in mind, the DOL properly explained their reasoning:

The extensive changes in the retirement plan landscape and the associated investment market in recent decades undermine the continued adequacy of the original approach in PTE 84–24. In the years since the exemption was originally granted in 1977, the growth of 401(k) plans and IRAs has increasingly placed responsibility for critical investment decisions on individual investors rather than professional plan asset managers. Moreover, at the same time as individual investors have increasingly become responsible for managing their own investments, the complexity of investment products and range of conflicted compensation structures have likewise increased. As a result, it is appropriate to revisit and revise the exemption to better reflect the realities of the current marketplace. 50

Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. Hugler, 231 F. Supp. 3d 152, 190-91

cChamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. Hugler, 231 F. Supp. 3d 152, 190-91 (N.D. Tex. 2017)

While not going into such valuable detail, Chief Judge Stewart expressed a similar rationale for upholding the Rule

Notwithstanding the DOL’s reasoned explanation for the new regulations, the panel majority maintains that the DOL acted unreasonably and arbitrarily when it promulgated the new fiduciary rule and, in a strained attempt to justify this conclusion, the panel majority disregards the requirement of showing judicial deference under Chevron by highlighting purported issues with other provisions of the regulation. Each of the panel majority’s positions fails for reasons more fully explained below.51

In light of changes in the retirement investment advice market since 1975,…, the DOL reasonably concluded that limiting fiduciary status to those who render investment advice to a plan or an IRA “on a regualr basis” risked leaving retirement investors inadequately protected. This is especailly so given that “one-time transactions like rollovers will involve trillions of dollars over the next five years and can be among the most significant financial decisions investors will ever make.52

The panel majority’s conclusion that the DOL exceeded its regulatory authority by implementing the regulatory package that included a new definition of investment-advice fiduciary and both modified and created new exemptions to prohibited transactions is premised on an erroneous interpretation of the grant of authority given by Congress under ERISA and the Code. I would hold that the DOL acted well within its regulatory authority—as outlined by ERISA and the Code—in expanding the regulatory definition of investment-advice fiduciary to the limits contemplated by the statute, and would uphold the DOL’s implementation of the new rules.54

When people ask me explain the case as simply as possible, my answer is that the annuity industry knows that it can never satisfy a true fiduciary standard that requires the industry to put the public’s “best interest” first, as its products and services are designed to maximize their profit to the detriment of plan participants and other investors. The annuity industry is well aware of these issues, thus the constant oppositon to a true fiduciary standard.

I do wonder if embracing the fiduciary standard and making some changes in annuity products might not acually open more, and profitable, markets for the annuity industry and increase profits. Some of my colleagues within the annuity industry have expressed similar thoughts.

Going forward , two of my favorite quotes come to mind, one from John Adams, the other from the late Genreral Norman Schartzkopf:

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence. – John Adams

The truth is, we always know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it. – General Norman Schwartzkopf

Stay tuned!

PostScript Late Friday it was announced that the DOJ would appeal both of the district court decisions vacating the Rule. There also reports that the parties were talking, hopefully about a resolution to the litigation. Hopefully, these reports are true. As well-known ERISA attorney, Bonnie Treichel, recently observed.

Arguably the most impacted parties then are the investors these individuals serve that aren’t provided service as an ERISA fiduciary.55

Notes

1. Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85, 90 (1983).

2. 5th Circuit, 47

3. 5th Circuit, 6

4. 5th Circuit, 47

5. 5th Circuit, 48-49.

6. 5th Circuit, 51.

7. 5th Circuit, 49.

8. 5th Circuit, 59

9. 5th Circuit, 60; 29 C.F.R.§ 2510.3-21(c)(1) (2015).

10. 5th Circuit , 60.

11. 5th Circuit, 62

12.Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. Hugler, 231 F. Supp. 3d 152, 190 (N.D. Tex. 2017) , 174 (C.J. Lynn)

13. C.J. Lynn, 167

14. C.J. Lynn, 170-171

15..C.J. Lynn, 171

16. C.J. Lynn, 64

17. C.J. Lynn, 170

18. C.J. Lynn, 171

19. C.J. Lynn, 173

20. C.J. Lynn, 173

21. C.J. Lynn, 172-173

22. C.J. Lynn, 173

23. C.J. Lynn, 174 n. 69

24. C.J. Lynn, 174 n. 69

25. C.J. Lynn, 174

26. C.J. Lynn, 175

27. C.J. Lynn, 188

28. C.J. Lynn, 188

29. C.J. Lynn, 188

30. C.J. Lynn, 186-187

31. C.J. Lynn, 189

32. C.J. Lynn, 188

33. C.J. Lynn, 188

34. C.J. Lynn, 189-190

35. C.J. Lynn, 190

36. C.J. Lynn, 190-191

37, 5th Circuit, 64

38. C.J. Lynn, 190-191

39. 5th Circuit, 10

40. Jeremy Babener, “Justifying the Structured Settlement Tax Subsidy: The Use of Lump Sum Settlement Monies,” NYU Journal of Law and Business Vol 6 (Fall 2009), (Babener)

41. Babener

42. 5th Circuit, 47-48

43. C.J. Lynn, 174

44. C.J. Lynn, 175

45. C.J. Lynn, 188

46. C.J. Lynn, 188

47. C.J. Lynn, 189-190

48. C.J. Lynn, 190

49. C.J.Lynn, 189-190.

50. C.J. Lynn, 89-190

51. C.J. Lynn, 190-191

52. C.J. Lynn, 190-191

53. 5th Circuit, 59

54. 5th Circuit, 59, 64

55. https://401kspecialistmag.com/erisa-attorneys-outline-next-steps-actions-item-after-dol-fiduciary-rule-stays/

The Fifth Circuit’s decision and Judge Stewart’s dissent: https://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/17/17-10238-cv0.pdf.

Judge Lynn’s decision: https://casetext.com/case/chamber-of-commerce-of-the-us-v-hugler

231 F.Supp. 3d 152

You must be logged in to post a comment.